An innovative water sharing program in India helps improve farmer livelihoods

Vanya Mehta of WELL Labs co-authored this blog.

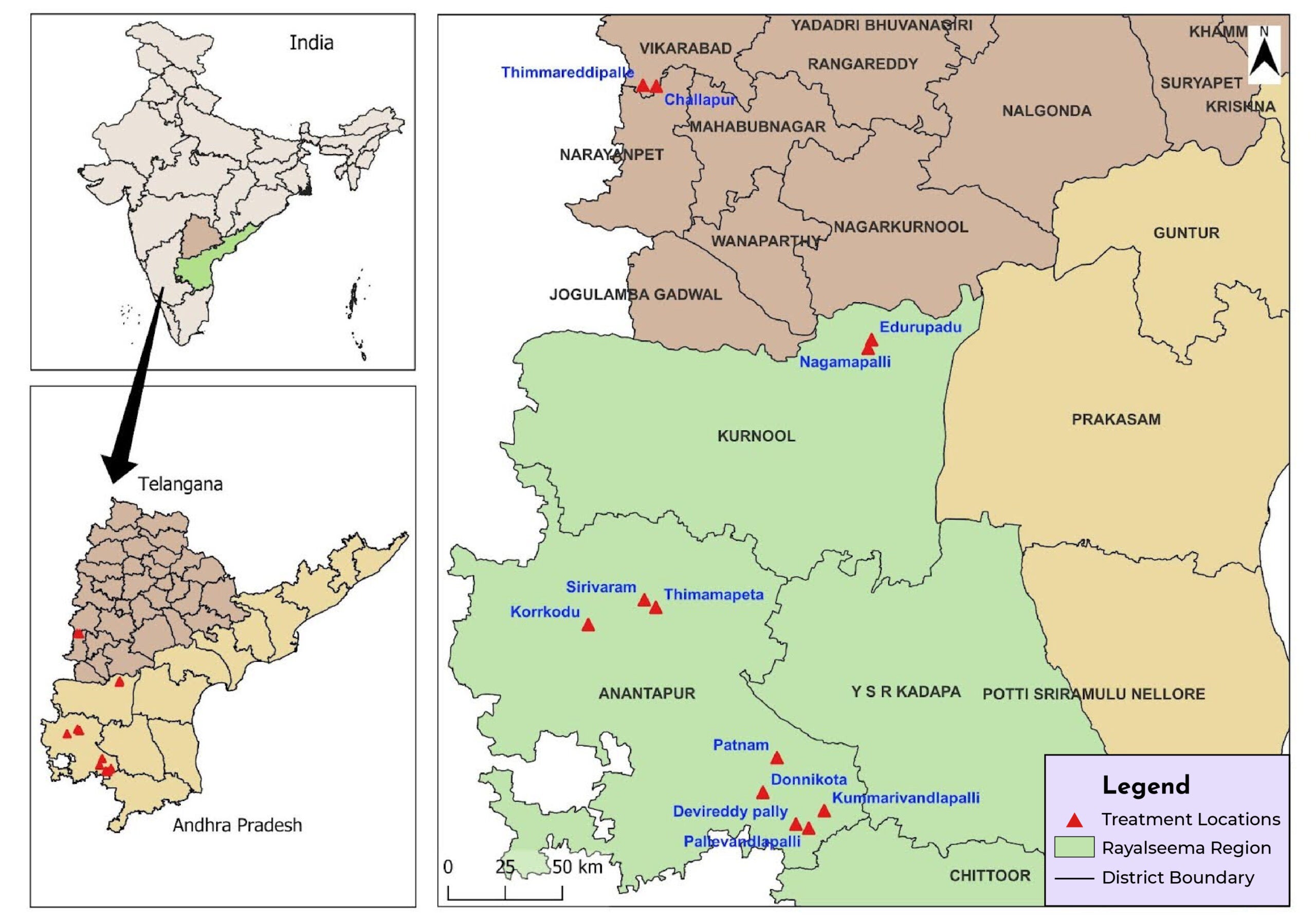

In a semi-arid region in southwest Andhra Pradesh, low but highly variable rainfall has made groundwater a critical lifeline for farmers.

But prolonged droughts and more borewell drilling have worsened groundwater depletion, severely impacting agrarian communities. To reduce competitive well drilling and assist farmers without wells in the region, the Watershed Support Services and Activities Network (WASSAN) launched the Groundwater Collectivization Programme. The initiative helps farmers form water collectives to share groundwater through formal agreements.

A new study of the Groundwater Collectivization Programme by researchers from EDF and WELL Labs revealed some encouraging results, including a slight increase in farm profits and higher yields during the monsoon season.

Water challenges in Andhra Pradesh

The semi-arid region of Rayalaseema in southwest Andhra Pradesh averages 270 dry days a year and 35 days with less than 2.5 millimeters of rain, resulting in an increasing reliance on groundwater for crop production.

Farmers with borewells irrigate in both the kharif (monsoon) and the drier rabi (winter) seasons, while those without borewells depend on rainfed farming, limiting their yields and income.

Canal irrigation is less common in the Rayalaseema region, leaving many farmers with groundwater as their only irrigation supply. In recent years, the number of borewells dug by farmers has increased significantly. Drilling a borewell is costly (between ₹80,000 and ₹1.5 lakh) and the borewell failure rate is high, due to the nature of granitic hard rock aquifers in the region.

Increasing irrigation equity during dry times

To motivate farmers who own borewells to share groundwater with non-borewell owning farmers, WASSAN proposed financing a piped network system to carry groundwater across multiple plots. This was attractive because borewell farmers often had non-contiguous plots that they were unable to irrigate during the rabi season.

The catch? Farmers only can access this financing for a piped network system if they agree to share water during monsoonal dry periods with all the members in the groundwater collective. The piped system was constructed with outlets into other farmers’ fields to enable this broader access to groundwater irrigation during water-scarce periods. As one farmer in Kumaravandlapalli explained, “Our lands are scattered, but after forming the water collectives, pipelines were extended to reach even the farthest fields.”

Additional conditions of the collective program included:

- A 10-year ban on drilling of new borewells within the group.

- Reduction of water-intensive cropping area, including a reduction of paddy cultivation by 50%.

- Adoption of water-saving technologies such as drip irrigation.

- Regular monetary contributions to maintain the shared pipelines and borewells.

- Commitments from borewell owners to provide protective irrigation during key crop stages in kharif and three to four times in rabi seasons.

Impact of the program

To determine the Groundwater Collectivization Programme’s effects on farmer livelihoods and water practices, EDF and WELL Labs conducted surveys, interviews, and focus group discussions with participants in the groundwater collectives (the “treatment” group) as well as farmers who did not participate (the “control” group). We collected data in 12 villages with established water collectives and 12 additional villages without collectives. Key findings include:

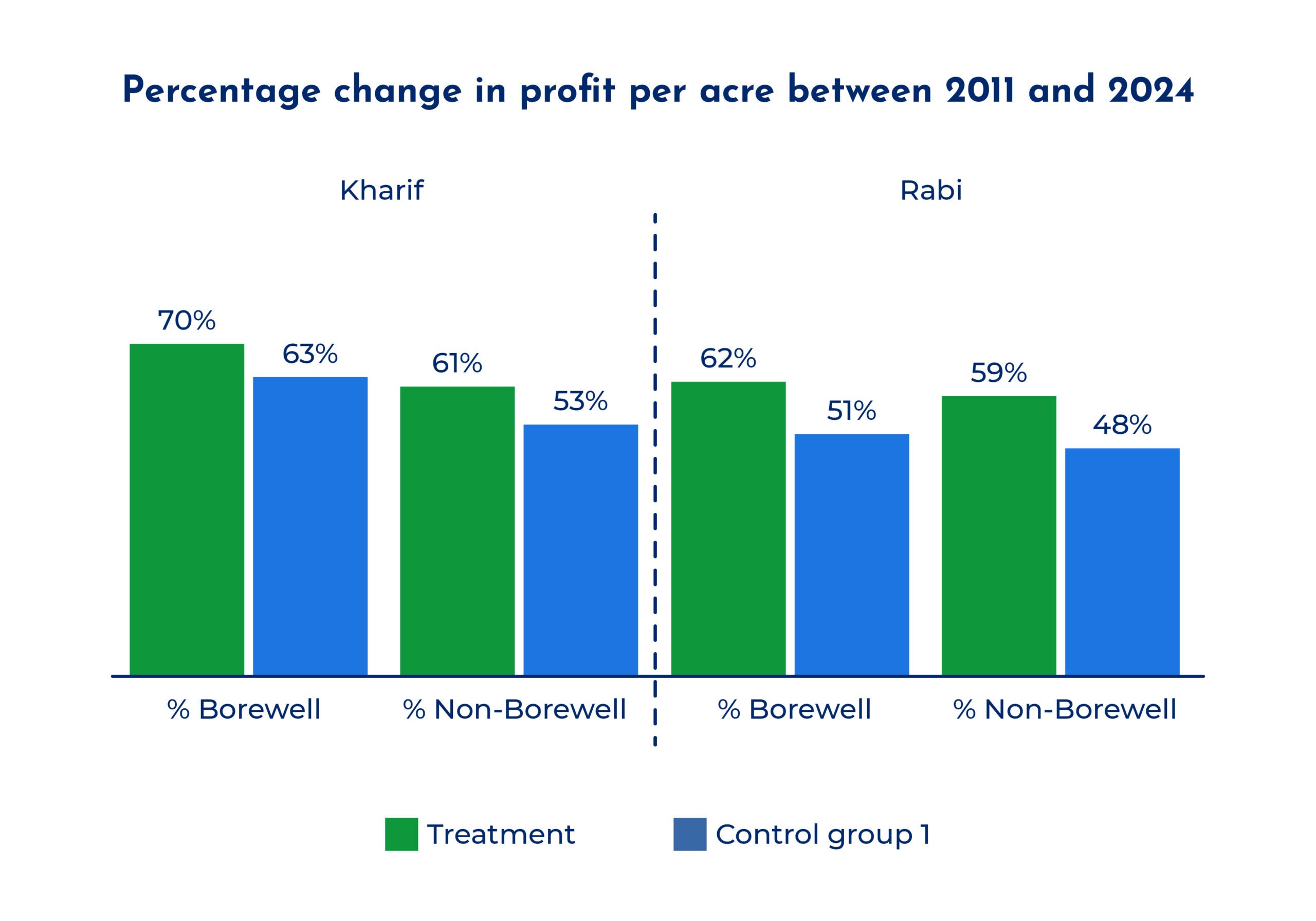

- Improved farmer income: After the WASSAN initiative began, farmers in the groundwater collective reported slightly higher profits compared to non-collective members. Borewell-owning collective members reported a 70% increase in profits, compared to 63% among non-collective borewell owners, while non-borewell collective members reported a 61% increase, versus 53% for non-borewell non-collective members.

- Improved access to irrigation: Farmers participating in the groundwater collective reported improved access to irrigation during the drier rabi season, enabling additional agricultural production. In 2011, before the WASSAN program, only one-third of farmers cultivated rabi crops. By 2023-24, 51% of groundwater collective members reported cultivating rabi season crops — an 18% increase.

- Reduced cultivation of water-intensive crops: The report categorized crops into low, moderate and high water-use groups. During the drier rabi season, farmers in the groundwater collective reported a 39% reduction in high water-use crops and a 35% increase in moderate water-use crops. This shift indicates progress toward more water-efficient farming practices. Consistent with this trend, paddy cultivation among collective members declined by 21%.

- Improved farmer productivity: Groundwater collective farmers reported a modest increase in rabi season yields relative to the non-collective farmers following the introduction of the WASSAN program. By 2023-24, borewell-owning collective members reported an 83% increase in yield, compared to a 73% increase among the non-collective group.

Enabling factors that led to the success of the program include:

- Land fragmentation: Borewell owners were able to irrigate their previously unirrigated, non-contiguous plots with the pipeline network, which incentivised them to share with the collective.

- Small and socially homogenous groups: Members of collectives at the village level were reported to be part of the same community, which allowed for more trust among the members.

Potential for scaling groundwater collectives in India

The WASSAN model of rewarding cooperation offers a practical way to reduce competition over groundwater and improve livelihoods. By extending irrigation to non-contiguous plots and enforcing rules against drilling new borewells, it promotes both economic and ecological benefits.

The model demonstrated success in improving livelihood outcomes for non-borewell owners in the collective and fostering groundwater management collaboration rather than competition. Although the collective did not reduce groundwater use overall, it did establish a social framework that could prove beneficial for layering on additional strategies to further improve groundwater management.

To strengthen and scale such efforts, we made two main recommendations in our study:

- Work at the aquifer-level: For groundwater collectives to impact groundwater levels, a program should be scaled to the aquifer level. Coordinated rules across all collectives within an aquifer can help prevent over-extraction by neighbouring farmers.

- Use technology for information sharing and monitoring: Technology can help share information and maintain compliance. For example, remote sensing can support the collection of large-scale data on water consumption and crop choice.

The WASSAN model demonstrates how social and physical infrastructure changes can lead to the collectivisation of groundwater resources. Ultimately, as we concluded in the report, a long-term approach that combines governance, policy incentives, and technology interventions will be essential for growing the Groundwater Collectivization Programme and ensuring that groundwater remains a shared, sustainable resource for future generations.