Observations from World Water Week: Indigenous voices gain center stage; groundwater remains largely overlooked

Last month EDF co-hosted a side event at World Water Week in Stockholm with an ambitious goal: to catalyze collaboration around a global movement to tackle the groundwater crises affecting many regions of the world.

The event, co-hosted with the International Water Management Institute (IWMI) and WELL Labs, addressed the need to raise the profile of the groundwater crisis at international water and climate change convenings like World Water Week, particularly given groundwater’s importance to food security, community health and livelihoods.

Despite the limited attention on groundwater at World Water Week, we observed other encouraging shifts at the conference this year, including the elevation of Indigenous voices and a greater focus on the connections between water resilience and climate change adaptation and mitigation. Here is a deeper look at these World Water Week highlights.

A core group of organizations is eager to elevate the groundwater crisis on the international stage.

World Water Week is packed with sessions from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. for five days, but only four sessions from the entire conference included the word “groundwater” in their title. Given that about 40% of our global food supply depends on groundwater and that many parts of the world are using groundwater far faster than it can be replenished, this underground water supply deserves far more attention. That was the consensus of the water leaders at our World Water Week side event, who represent such organizations as the World Bank, Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), University of Arizona, University College London, Daughtery Water for Food Global Institute, and The Nature Conservancy.

Mark Smith, director general of IWMI, suggested that groundwater’s lack of visibility in international dialogues may stem from its invisibility on a few fronts. It’s not mentioned specifically in U.N. Sustainability Goal 6, focused on clean water and sanitation for all. And of course, groundwater depletion is invisible because the water is underground, in sharp contrast to when a reservoir experiences declining water levels or a river even dries up altogether. altogether.

Veena Srinivasan, executive director of WELL Labs, facilitated a discussion about the challenges that farmers, communities, and governments face in managing groundwater. She highlighted two challenges in India: Government electricity subsidies have led to rampant groundwater overextraction, and some farmers with a more shortsighted view of farming don’t envision passing their farms down to their children. Consequently, they are less concerned about ensuring there is enough groundwater for future generations.

The group discussion that I facilitated focused on sharing examples of promising groundwater management interventions. The discussion revealed that there are many examples but few that are holistic, addressing not only groundwater depletion but related economic and environmental issues . A few examples that stood out include “green roads” to maximize groundwater infiltration and recharge in Nepal, cropswitching from rice to wheat in Bangladesh, changes to pricing to pump groundwater in Thailand that led to greater conservation, and an “ATM” system for wells in China that includes a card with a water quota and fines if that quota is exceeded.

Water management can contribute to climate change mitigation and adaptation.

“The water crisis is a climate crisis,” Helena Thybell, executive director of the Stockholm International Water Institute, said during her opening remarks at World Water Week. “Water Is not just part of the climate story; it is the key to rewriting it.”

Many speakers throughout the conference echoed those sentiments and noted how water strategies can both mitigate climate change (in other words, reduce greenhouse gases) and help communities adapt to climate change. During a session that I participated in titled “Water for food in a changing climate: Pathways to adaptation and mitigation,” I had the opportunity to share how some projects in California are examples of both climate adaptation and mitigation.

During the panel discussion, I shared how California’s Sustainable Groundwater Management Act mandates the reduction of groundwater use while the state’s Multibenefit Land Repurposing Program aims to deliver new benefits that can help farmers adapt to using less water. These programs also have a co-benefit of helping to mitigate climate change. For instance, farmers who are adapting to climate change by pumping less groundwater are lowering their electricity use, thus reducing emissions. And going one step further, some farmers in California are replacing their crops with solar farms, generating renewable energy and ultimately helping the state move closer toward its 2045 carbon neutrality goal.

My fellow panelist Nicole Silk from the Nature Conservancy and other speakers also emphasized the role of nature-based solutions in conserving water and supporting ecosystems.

Indigenous leaders had a larger presence than ever.

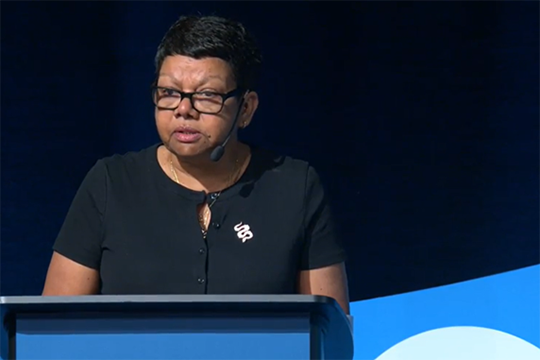

Surprisingly and belatedly, this was the first World Water Week that featured a main stage, high-level session with Indigenous leaders, primarily from Canada, Australia and Scandinavia.

“Nothing about us without us” should be the standard for including Indigenous communities in water decision making and management, said Kay Blades, a Mandandanji woman and member of the Committee on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Water Interests (CAWI) in Australia.

“Greater trust in Indigenous knowledge and skills is essential, particularly in areas like natural resource management. Indigenous knowledge systems developed over centuries offer valuable insights into sustainable practices that can complement if not lead mainstream methods.”

The conference also featured more corporate voices.

We were also encouraged by the number of sessions on corporate water stewardship, including one particularly practical session on freshwater science-based targets for business resilience. During the session, water leaders from such companies as Kering and Gap Inc. talked about their efforts to track water use and support local communities. Their insights were particularly useful as we explore how we can collaborate with corporate water stewardship leaders to advance sustainable, long-term water and land management.

The 2026 U.N. Water Conference should focus on holistic water management and groundwater.

Collaboration and partnership have long been buzzwords at World Water Week, but the more prominent presence of both Indigenous leaders and the corporate sector may be encouraging signs of meaningful progress. In addition, the conference this year featured more discussion of the need to break down the siloes between water, food, land management and policy a— and even tourism in the case of island nations.

We certainly hope that the discussions at World Water Week pave the way for water, land, food and climate change to be considered more holistically at the 2026 U.N. Water Conference — and that groundwater also gains the attention it deserves — as taking this more holistic approach that also includes groundwater is the most promising path toward a thriving future for the many regions that are currently facing a dire water crisis.