Tackling Methane isn’t just good for the climate — it disproportionately protects the global poor

This blog was authored by Anshuman Tiwari, who is currently a Postdoctoral Research Scholar at the Energy Policy Institute at the University of Chicago (EPIC India) and was formerly a Postdoctoral Fellow jointly at the Environmental Defense Fund and the Environmental Markets Lab at UC Santa Barbara.

Global climate negotiations often focus on where we end up, for example, the 1.5°C target set by the Paris agreement. But there’s a crucial detail hiding in plain sight: how quickly we reduce warming on the way to that target can dramatically reduce the incidence of climate impacts on the global poor. Our new analysis puts numbers on that intuition by tracking the effect of climate change on a most personal outcome: human lives. Sustained cuts to methane emissions starting today saves many more lives compared to delaying action — and those lives are disproportionately in the places most vulnerable to climate change.

The same 2100 temperature, very different human outcomes

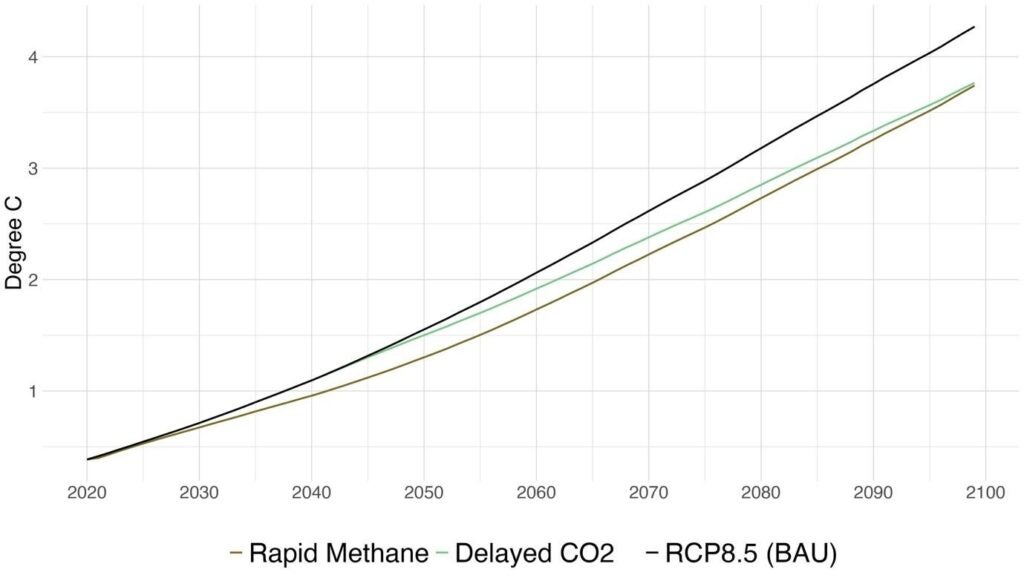

We compare six mitigation pathways — avoiding methane (CH₄) and carbon dioxide (CO₂) emissions, each implemented rapidly, slowly, or with a delayed start — designed so they all reach the same global temperature outcome in 2100. This matters because it isolates something policy debates often gloss over: timing. If two strategies hit the same end-of-century target, it’s tempting to treat them as roughly equivalent, particularly if one of them delays costly mitigation. Figure 1 shows warming under business as usual, and two of these scenarios: rapid methane mitigation and delayed CO₂ mitigation.

Fig 1: Global warming trajectories under BAU and mitigation pathways.

Source: Carleton and Tiwari (2025), Rapid and Sustained Cooling Reduces Global Inequity in Climate Impacts. Manuscript under preparation.

Why methane emissions matter

Methane is uniquely powerful for near-term cooling because it’s short-lived in the atmosphere — roughly two decades— and extremely potent over that time frame. That means cutting methane can deliver faster, earlier cooling, while CO₂ reductions—essential and non-negotiable for long-run stabilization—often translate into benefits that accumulate more gradually. Rapid methane mitigation yields immediate, substantial cooling benefits; CO₂ pathways matter enormously but tend to shift more of their temperature payoff later. We borrow our Methane scenarios from earlier work done by EDF scientists, and design CO₂ pathways that follow similar avoided emissions trajectories. Crucially, these emissions reductions must be sustained over time for climate benefits to be sustained.

How we estimates temperature-related lives saved from avoided warming

Our work builds on state-of-the-art mortality impact projections from Carleton et al (2022), contributing something many climate damage calculations still miss: fine-grained heterogeneity across space and time. Both space and time are important as we let the evolving climate and income levels mediate the effect of climate change on mortality, thus allowing for adaptation. We construct mortality “damage functions” with adaptation for ~25,000 subnational regions worldwide for every year from 2025–2100, aggregating future uncertainty in climate projections and economic damages. The average region has a slightly larger population than the average US county today. We rank these regions by their income per capita in 2020, and conduct equity analysis based on this measure. The regional damage functions capture the mortality effect of direct exposure to temperature extremes, as well as indirect channels such as crop failures. We then combine those region-year relationships with modelled temperature trajectories under each mitigation pathway to translate cooling into lives saved and various equity metrics (for eg. benefits accruing to the poorest 20% world regions).

The poorest regions of the world based on income per capita are also where most of the global poor live. Various studies have found that these groups are also the most vulnerable to the effects of climate change (Hallegatte et al, 2016). Richer places can invest in technologies to reduce vulnerability to temperature-related effects while hotter places change economic structures to adapt to their climate. We focus on these mediators since they capture much of historical adaptation and can be more easily projected for the future. In particular, today’s poor places are projected to get richer, and we incorporate this improvement in our analysis.

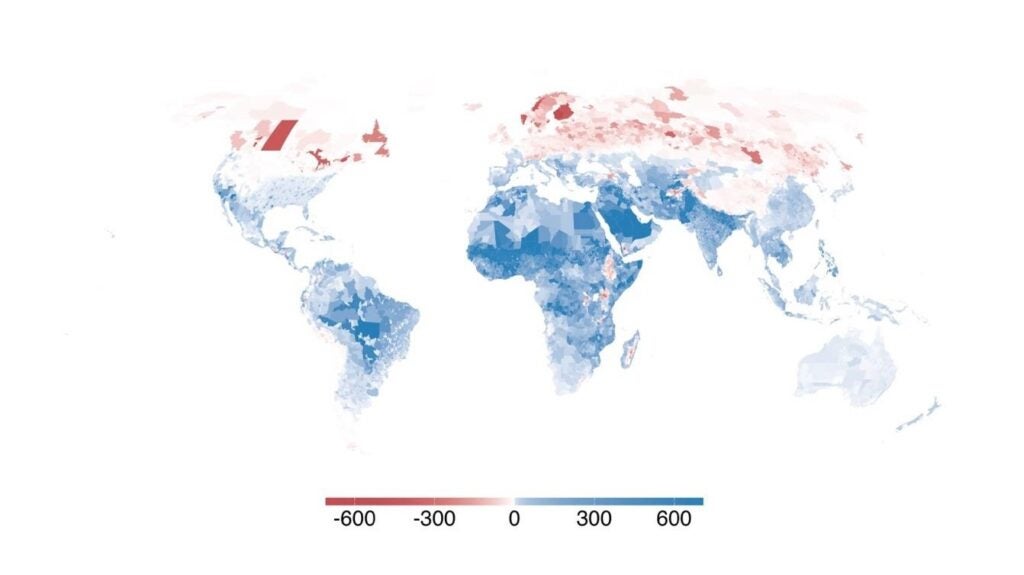

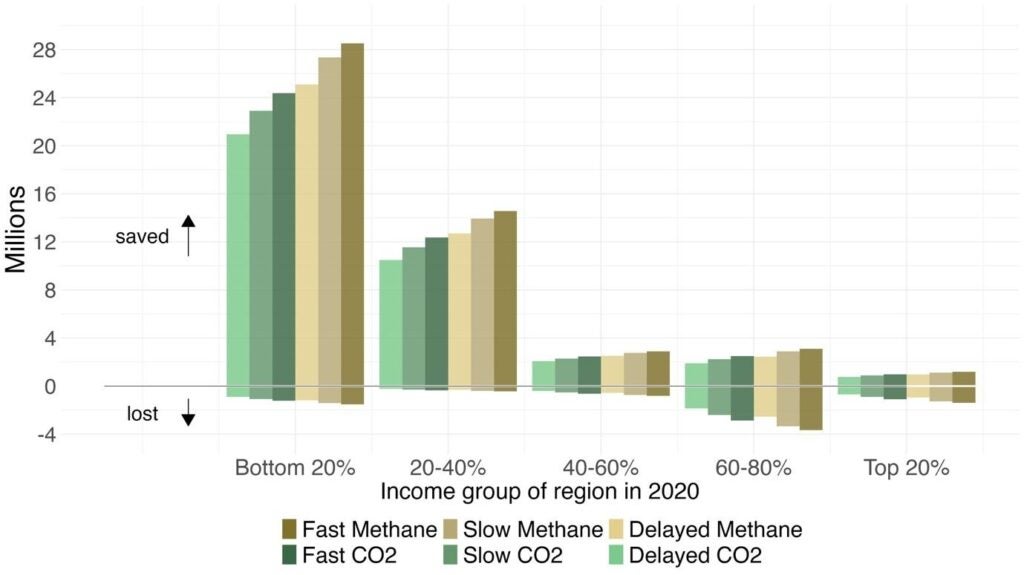

Rapid action saves more lives where vulnerability is greatest

We find that mitigation improves global equity in mortality outcomes in every scenario, relative to no action. We also find that the least effective Methane pathway in terms of lives saved is more effective over the century compared to the most effective CO₂ pathway — because earlier cooling sustained over time prevents more harm. But the real story here is about where those lives are saved. Under rapid methane mitigation, the poorest 40% of the world today accounts for 85% of all lives saved globally. Compared to delayed CO₂ mitigation, 12 million more lives are saved in these poorest regions from rapid methane mitigation until 2100.

In other words: rapid methane action doesn’t just produce immediate climate benefits. It’s also distributionally progressive in human terms. It directly speaks to global equity—places least responsible for historical emissions are projected to bear the largest harms, and earlier cooling lessens that burden.

On the other hand, climate-related deaths do occur in colder, richer regions, largely due to prolonged exposure of older people. Some of these regions are projected to see fewer deaths as winters warm due to climate change. That means mitigation can reduce that benefit, showing up as “lives lost” relative to a warming baseline. We show that these losses in rich regions are dwarfed by the gains in poor places. But this may not need to be a trade-off. For example, a potential strategy for high-income, low-growth countries could be to generateing higher returns by investing their savings in the energy transition already underway in low-income, high-growth places. This may allow today’s cold regions to underwrite policy responses such as better housing or heating that could substantially reduce mitigation-related losses.

Fig 2: Number of lives saved in 2100 under rapid methane mitigation

Source: Carleton and Tiwari (2025), Rapid and Sustained Cooling Reduces Global Inequity in Climate Impacts. Manuscript under preparation.

Fig 3: Total lives saved between 2025-2100, by baseline income in 2020

Source: Carleton and Tiwari (2025), Rapid and Sustained Cooling Reduces Global Inequity in Climate Impacts. Manuscript under preparation.

Policy implications

Our analysis lands on a simple but politically important point: mitigation pathways matter, not just the endpoint. If global priorities include equity—taking seriously “common but differentiated responsibilities”—then rapid and sustained methane abatement should be a core pillar of an equity-first strategy that accelerates decarbonization.

What does “rapid methane abatement” look like in practice? Near-term methane reductions are heavily driven by actions like controlling oil and gas leaks. As noted in this EDF explainer, the oil and gas industry can achieve a 75% reduction using technologies available today. These reductions can be complemented by targeted interventions in landfills and livestock.

That lines up with a pragmatic reality: many methane cuts are available now, and a lot of them come with clear measurement and enforcement pathways. Pairing these pathways with smartly financed clean energy deployment in developing countries will generate the benefits our study highlights: more vulnerable lives saved alongside potential returns to clean energy investments. While this blog focuses on the often overlooked role of timing and its relationship to equitable climate outcomes at a global level, we acknowledge that a just approach to mitigation also requires attention to where and how emissions reductions occur, which has important implications for economic conditions and localized environmental impacts.