From model to policy: Building a climate connection between modelers across the world

This blog was authored by Francisco Pinto, economist with the Climate Action Teams (CAT) initiative, Catherine Leining, Policy Fellow at Motu Economic and Public Policy Research, and Luis Fernández Intriago, economist at Environmental Defense Fund.

As record-breaking heatwaves, wildfires, and floods make headlines around the world, one thing is clear: climate action can’t wait, and no country can tackle the challenge alone. Meeting global climate goals will take not just political will, but better tools to guide smarter decisions, especially in crucial sectors like energy.

That is why researchers from CAT and Motu Research recently convened experts from Chile and Aotearoa New Zealand to discuss economic modeling challenges and needs for developing national mitigation targets. Participants considered how countries can learn from one another to build more effective, practical pathways to decarbonization, with a particular focus on the energy sector.

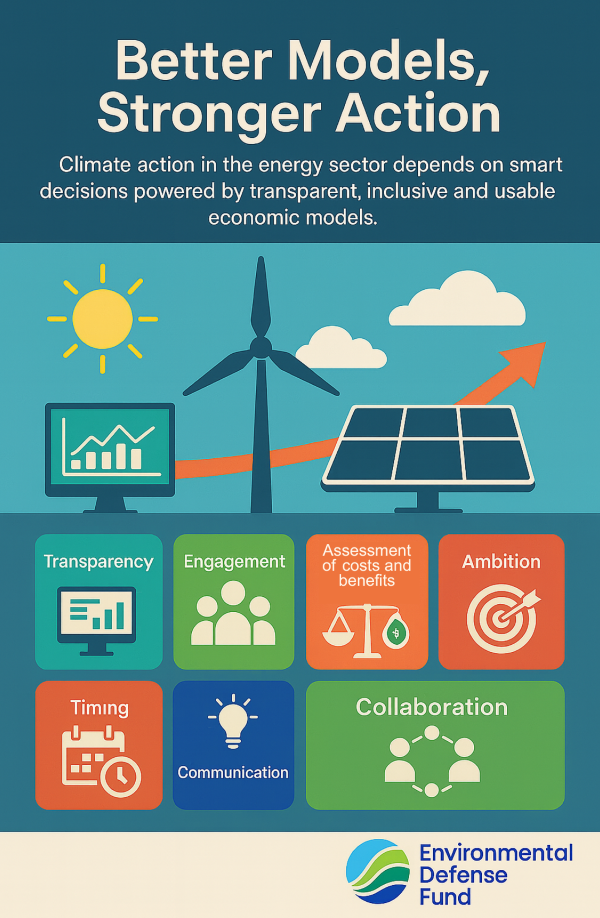

In both countries, economic modeling of decarbonization pathways has evolved considerably over recent years to support decision-making under the Paris Agreement. A rich exchange of ideas emerged on ways to strengthen the link between economic modeling and effective climate policy, with a central thread of how modeling outputs can be made more usable for policymakers. The group identified seven areas to bridge that gap, offering a clear roadmap for turning complex analysis into clearer, faster climate decisions.

Transparency: One of the clearest takeaways was the need for greater transparency and accessibility for modeling work. Participants stressed that open access to models—especially official ones—and clear documentation of data and assumptions would make it easier for independent researchers to compare results from different models, identify common findings, and understand divergences. Many pointed to the value of applying high-quality open-source tools to help accelerate progress, noting the need to adapt them carefully to each country’s context.

Engagement: There was a strong call to involve a broader set of actors in the modeling process, particularly policymakers and affected stakeholders who will ultimately be impacted by the policies being modeled. Including them in data collection, scenario-building, and defining assumptions can boost the legitimacy of results, build public trust, create a more informed base for sharing findings, and ensure that modeling exercises address crucial policy questions.

Assessment of costs and benefits: Participants emphasized that modeling should go beyond conventional cost analysis to capture co-benefits (e.g., for human health, air and water quality and biodiversity). Modeling should also provide insights not only on the total GDP impacts of alternative decarbonization pathways, but also on how the costs and benefits are distributed across different populations, sectors, and generations. This approach can deepen understanding of employment impacts and support just transition planning for workers in carbon-intensive industries. Importantly, modeling can also help decision-makers weigh the often-overlooked costs of inaction or delay.

Ambition: Several participants highlighted the importance of modeling a range of ambitious decarbonization pathways, including those supported by bold policy, stronger finance, and technological change to reveal what’s truly possible with greater political will and international cooperation.

Timing: For modeling to be a useful input in decision-making, timelines must be aligned. Policy processes need to allow sufficient lead time for modeling, and modelers need sustained resources to keep tools updated across decision-making cycles.

Communication: Because modeling is often technical and complex, clear communication is essential. Translating modeling results into compelling narratives about future options and tradeoffs can make them more digestible. Participants also stressed the importance of explaining uncertainty in practical terms—what we know, what we don’t, and what’s within policymakers’ control. Managing expectations is equally important: models aren’t crystal balls. In reality, they offer valuable guidance to help us make informed choices today.

Collaboration: Finally, the workshop underscored the real-world value of international collaboration. Across countries, sharing lessons, whether about technical challenges, policy design, or using Article 6 of the Paris Agreement for international mitigation transfers, can save time, close knowledge gaps, and lead to better outcomes. But beyond the technical value, participants also highlighted the power of connection. Knowing that others are working toward the same goals can itself be motivating. As one participant noted, even moral support can have a lasting impact.

Exchanges like these show that sharing models also means connecting minds. That, in turn, can lead to smarter, more ambitious climate action.

The session sparked participants’ interest in strengthening international collaboration between modelers. Prototypes for this kind of collaboration are already underway. For example, EDF leads the Multi-Country Electricity Transition (MCET) Network, which brings energy modelers together with policymakers and advocates from ten countries to identify effective pathways for decarbonizing energy generation.

Although models cannot predict the future, they can help us prepare for it. And when those who develop them do so together, across borders, the path to real solutions becomes much clearer.

Climate Action Teams and Motu Economic and Public Policy Research are two not-for-profit organizations based in Chile and New Zealand, respectively. Among other initiatives, they work to promote international collaboration to address climate change. Funding for the workshop was provided by the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) and facilitation support was provided by the Consensus Building Institute (CBI).