EPA’s safety standard for perchlorate in water should prioritize kids’ health

Tom Neltner, J.D., is Chemicals Policy Director and Maricel Maffini, Ph.D., Consultant

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) will soon propose a drinking water standard for perchlorate. The decision – due by the end of May per a consent decree with the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC)— will end a nearly decade-long process to regulate the chemical that has been shown to harm children’s brain development.

In making its decision, EPA must propose a Maximum Contaminant Level Goal (MCLG) “at the level at which no known or anticipated adverse effects on the health of persons occur and which allows an adequate margin of safety.”[1] It must also set a Maximum Contaminant Level (MCL) as close to the MCLG as feasible using the best available treatment technology and taking cost into consideration.

To guide that decision, EPA’s scientists developed a sophisticated model that considers the impact of perchlorate on the development of the fetal brain in the first trimester when the fetus is particularly vulnerable to the chemical’s disruption of the proper function of the maternal thyroid gland. As discussed more below, the model was embraced by an expert panel of independent scientists through a transparent, public process that included public comments and public meetings.

In April, a consulting firm published a study critiquing EPA’s model. The authors acknowledged the model as a valuable research tool but did not think it is sufficient to use in regulatory decision-making due to uncertainties. Therefore, the authors concluded that EPA should discard the peer-reviewed model and rely on a 14-year old calculation of a “safe dose” that does not consider the latest scientific evidence and has even greater uncertainties. They didn’t offer other options such as using uncertainty factors to address their concerns about the model’s estimated values.

Given the importance of the issue and the risk to children’s brain development, we want to explain EPA’s model, the process the agency used to develop it, and the study raising doubt about the model.

EPA’s model quantifies the relationship between perchlorate and fetal brain development

The model involves two steps. First, it links a pregnant woman’s exposure to perchlorate in the first trimester to the chemical’s impact on levels of a thyroid hormone known as free T4 (fT4). Second, it links decreased fT4 levels to negative effects on IQ, motor skills, cognitive and language development, reaction times in children. The result of the model is a quantitative relationship between maternal perchlorate exposure and harm to the fetal brain – which is important to understanding the risk posed by this chemical and to evaluating various regulatory options.

In a November 2017 blog, we applauded EPA’s scientists for developing the model, noting that:

A 1% shift in the population of women with hypothyroxinemia [low fT4] associated with perchlorate exposure would correspond to an increase of 4,000 impacted children; if there is a 5% shift, the number of impacted children born to hypothyroxinemic mothers would increase to 20,000.

While these percentages appear small, they represent a significant number of potentially affected children since neurodevelopmental harm is likely irreversible. According to the model, the 1% shift corresponds to an exposure of 0.3 micrograms of perchlorate per kilograms of body weight per day (µg/kg-bw/day). The 5% shift corresponds to 2.1 µg perchlorate/kg-bw/day. These exposure levels do not include uncertainty factors or provide “an adequate margin of safety” as required by law.

EPA followed an extensive public process to develop the model

EPA went through an arduous process that involved extensive review by independent scientists to develop the model. In 2013, its Science Advisory Board (SAB) reviewed an agency proposal to develop an MCLG and concluded EPA needed to do more to protect fetal brain development. The SAB directed the agency to focus on the more sensitive measure of thyroid dysfunction called hypothyroxinemia (i.e., low fT4 levels) because of its expected impact on the developing brain.

In 2016, EPA developed a Biologically-Based Dose Response Model (BBDR) that focused on the third trimester and breast-fed infants. A peer review panel, convened by the agency, provided positive feedback but challenged the agency to focus on the first trimester when the fetus is most vulnerable to hypothyroxinemia. In 2017, EPA rose to the challenge and refined the BBDR model for the first trimester after conducting a rigorous review of the science. It also drew on five distinct children studies showing a quantitative relationship between perchlorate exposure, low fT4 and harm to the developing brain.

After another round of public comments, the agency reconvened the peer review panel. In March 2018, the panel gave what amounts to high praise coming from independent scientists convened to be critical of the agency’s work. It said:

Overall, the panel agreed that the EPA and its collaborators have prepared a highly innovative state-of-the-science set of quantitative tools to evaluate neurodevelopmental effects that could arise from drinking water exposure to perchlorate. While there is always room for improvement of the models, with limited additional work to address the committee’s comments below, the current models are fit-for-purpose to determine an MCLG.

Critique of EPA’s model claims too much uncertainty to be useful

The American Water Works Association, a 501c(3) technical and education organization representing drinking water professionals and utilities that would be affected by the rule, funded a consulting firm, Ramboll, to evaluate EPA’s model. The authors of the report attempted to recreate the BBDR model and, in the study published in April 2019, they concluded that:

While the USEPA (2017) BBDR model represents a valuable research tool, the lack of supporting data for many of the model assumptions and parameters calls into question the fitness of the extended BBDR model to support quantitative analyses for regulatory decisions on perchlorate in drinking water. Until more data can be developed to address uncertainties in the current BBDR model, USEPA should continue to rely on the RfD [reference dose] recommended by the NAS [National Academy of Science] (USEPA, 2005) when considering further regulatory action.

In essence, rather than offering a solution to address uncertainties, the authors proposed ignoring new, compelling evidence that perchlorate exposure during pregnancy harms the developing brain. Instead, they called for EPA to use an RfD developed in 2005 that was estimated using a study of healthy non-pregnant adults, that evaluated a less-sensitive effect and that had added a 10-fold intraspecies uncertainty factor to protect the most sensitive subpopulation, the developing fetus.

The authors’ conclusion is at direct odds with those made by EPA’s independent peer-review panel through a multi-year transparent public process, which acknowledged the uncertainties but deemed them adequately addressed by the agency’s model. The recommendations appear to be an unrealistic demand for perfection. EPA’s model represents the “best-available, peer reviewed science,” which the Safe Drinking Water Act requires EPA to base its decisions upon.

To provide an ample margin of safety, EPA should adopt an RfD of 0.03 µg/kg-bw/day

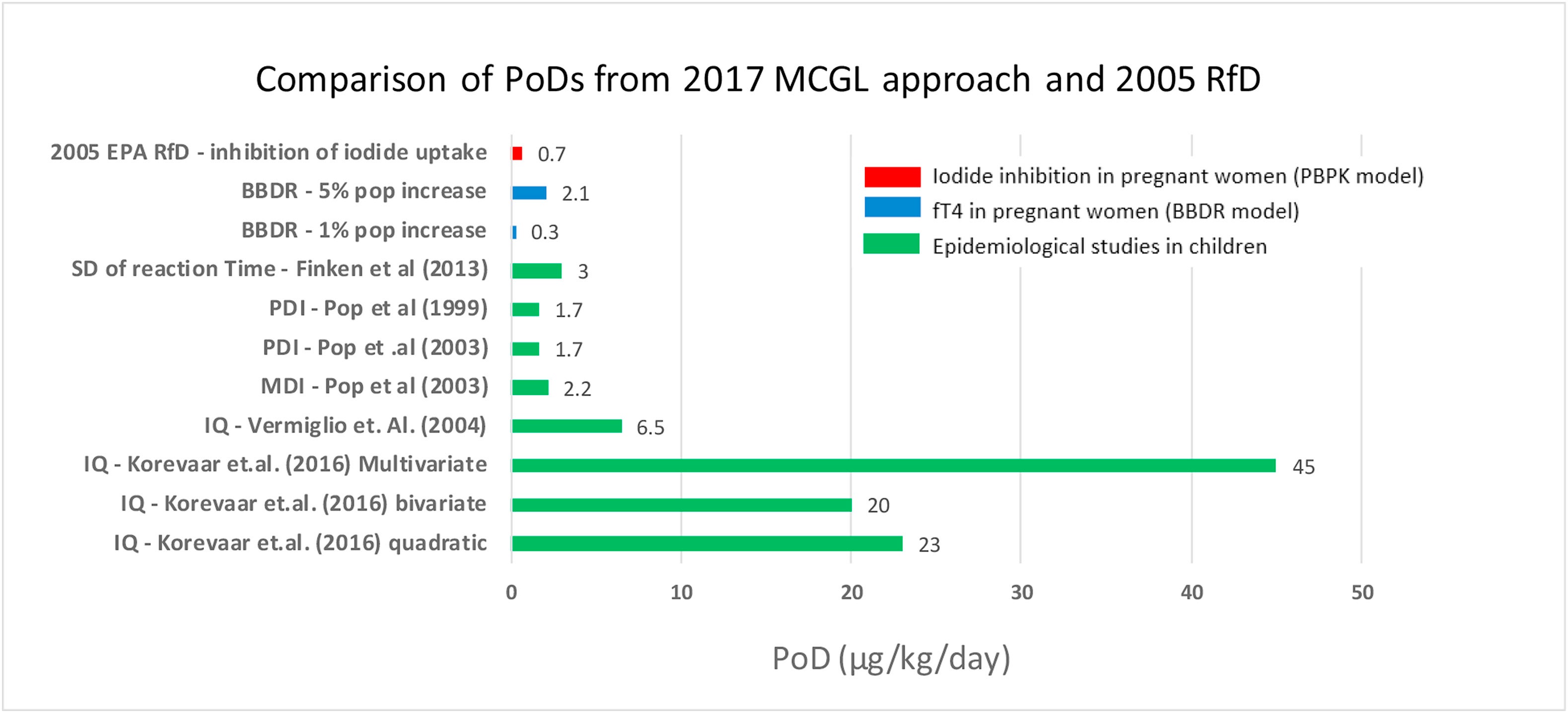

The graph below, copied from the Ramboll study, provides a helpful comparison between the various “Points of Departure” (PoD) (green and blue bars) and the current RfD (red bar). According to EPA’s Integrated Risk Information System (IRIS) Glossary, a PoD is “the lower bound on dose for an estimated incidence or a change in response level from a dose-response model” such as the one EPA developed. In contrast, the RfD is the lowest PoD “with uncertainty factors generally applied to reflect limitations of the data used.” The green bars represent points of departure based on the five epidemiological studies in children that EPA and peer reviewers considered sufficient on which to build the model. The blue bars show the model’s PoD for the 1% and 5% increase in pregnant women population becoming hypothyroxinemic without any additional factors to address uncertainties in the model. The red bar is the current RfD developed in 2005 that incorporates an uncertainty factor to protect the developing fetus.

Rather than discard the sophisticated model developed by EPA’s scientists because of recognized uncertainties, the agency should use 0.3 µg/kg-bw/day as the PoD since this is the lowest dose for which the model shows a change in fT4 level. To calculate the RfD, we recommend an additional 10-fold safety factor based on four considerations:

- The uncertainties identified by EPA, its independent review panel, and the Ramboll study’s authors.

- The reported variability in women’s iodine consumption and trend towards lower iodine consumption in women of childbearing age, that would make the risk from perchlorate exposure even greater.

- The measured adverse effects may only be indicators for other developmental problems. While the effects identified by EPA represent endpoints that have been standardized and commonly measured, they are likely only a few of the potential additional effects that be occurring.

- Most importantly, the developmental effects may be irreversible.

Therefore, based on our calculations, the RfD should be 0.03 µg/kg-bw/day – about 20 times more protective than the current reference dose. We believe this RfD better “allows an adequate margin of safety” as required under the law.

When EPA publishes the proposed MCLG by the end of May, we will learn whether EPA puts children’s health first.

2 Comments

Thanks for this update Tom. We deal in water filtration and wrote about this approx 7 years ago when we thought that the lack of regulation was out of hand. The fact that this has still not be regulated properly in 2019 is sad, but not surprising. I think your RfD of .03 µg/kg-bw/day makes a lot of sense for the reasons you lay out. There’s simply not much of this out in regards to scientists recommendations on proper regulations of percolate or many others chemicals that continue to contaminate our water sources. We’ll be checking back in here and writing a follow-up article for our visitors and customers once the new EPA proposal is released. Thanks again!

According to #5 on page 4 of the Consent Decree: “No later than December 19, 2019, EPA shall sign for publication in the Federal Register a final MCLG and NPDWR for perchlorate.” Why do you say in the second sentence that the decision is now due at the end of May?