Little follow-up when FDA finds high levels of perchlorate in food

Tom Neltner, J.D., is Chemicals Policy Director and Maricel Maffini, Ph.D., Consultant

[pullquote]FDA’s apparent lack of follow-up when faced with jaw-dropping levels of a toxic chemical in food is disturbing.[/pullquote]

For more than 40 years, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has conducted the Total Diet Study (TDS) to monitor levels of approximately 800 pesticides, metals, and other contaminants, as well as nutrients in food. The TDS’s purposes are to “track trends in the average American diet and inform the development of interventions to reduce or minimize risks, when needed.” By combining levels of chemicals in food with food consumption surveys, the TDS data serve a critical role in estimating consumers’ exposure to chemicals.

From 2004 to 2012 (except for 2007), FDA collects and tests about 280 food types for perchlorate, a chemical known to disrupt thyroid hormone production. This information is very important, because for the many pregnant women and children with low iodine intake, even transient exposure to high levels of perchlorate can impair brain development.

The agency published updates on food contamination and consumers’ exposure to perchlorate in 2008 (covering years 2004-2006) and in 2016 (covering 2008-2012). On its Perchlorate Questions and Answers webpage, FDA says it found “no overall change in perchlorate levels across foods” in samples collected between 2008 and 2012 compared to those collected between 2005 and 2006. It also notes that there were higher average levels in some food and lower in others between the time periods and suggests that a larger sampling size or variances in the region or season when the samples were collected may account for the differences.

FDA’s Q&A webpage masks the most disturbing part of the story

FDA’s attempt at providing consumers with information about the presence of a toxic chemical in food and what it means for their health falls short. By focusing on the similar average level of perchlorate across foods, FDA masks the disturbing fact that children are consuming increasing amounts of perchlorate: 35% for infants, 23% for toddlers and 12% for children between 2 and 6 from 2004-2006 to 2008-2012. The agency’s webpage notes the exposures in 2008-2012 but fails to mention the increase reported by its own scientists.

FDA’s webpage also fails to mention that the perchlorate Reference Dose (RfD), the amount of exposure unlikely to result in an adverse health effect, was set more than a decade ago and does not reflect the latest research. In 2013, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)’s Science Advisory Board indicated that the RfD may not sufficiently protect pregnant women and young children. As a result, EPA, with FDA’s support, is in the final stages of updating that number. FDA’s estimated average exposures to perchlorate by infants and toddlers was very close to the RfD, and many children may well exceed the outdated RfD.

FDA failed to investigate extraordinarily high levels of perchlorate

In the 2016 update, we noticed that some foods, such as bologna, salami and rice cereal, had very high levels, far greater than in 2004-2006. In May 2017, FDA provided more data that enabled us to learn what region and year the samples were collected.

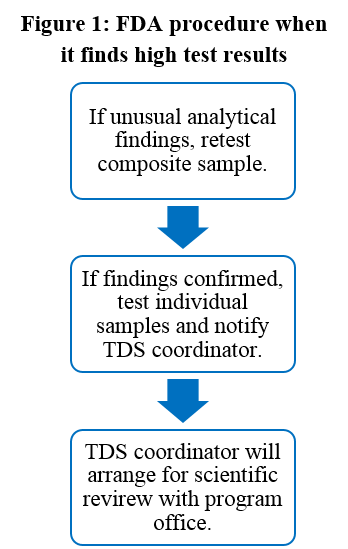

We knew from FDA’s Compliance Program Guidance Manual that staff are asked to follow-up on any unusual analytical findings in the TDS samples (Figure 1). So in June 2017, we filed a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request seeking details for 47 composite samples (18 baby foods and 29 other foods) that, in our view, had unusually high levels of perchlorate. We asked for any information regarding:

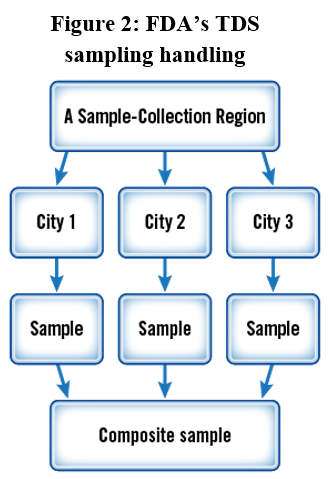

- Test results for composite and individual samples (Figure 2);

- Product details on the individual foods; and

- Any follow-up testing or investigations.

FDA’s response to the FOIA raises concerns. First, the agency did not have criteria for following up on perchlorate. Specifically, staff requested guidance “on cut-off value of perchlorate in the composite that would trigger analysis of individual foods,” but we didn’t find any in the documents provided to us. Without this guidance, some staff listed composite samples with at least 20 ppb as “noteworthy;” others used 15 ppb as the trigger for re-testing and confirmation. All 47 samples we asked FDA about were above these levels. Yet, there was no retesting of the composite for 27 of them.

Second, staff confirmed the results for 20 composite samples which should have triggered tests on the three individual samples that made up the composite.

But FDA only provided information for four individual foods:

- Baby food rice cereal (173 ppb in c

omposite in summer of 2008): Newark sample had 252 ppb; New York City had 112 ppb; and Philadelphia had 3 ppb.

omposite in summer of 2008): Newark sample had 252 ppb; New York City had 112 ppb; and Philadelphia had 3 ppb. - Baby food carrots (74 ppb in composite in winter of 2011): Denver sample had 163 ppb; Los Angeles sample had 111 ppb; and Seattle sample had 0 ppb.

- Baby food barley cereal (67 ppb in composite in spring of 2008): Dallas had 182 ppb; and Tampa and Baltimore had 1 ppb.

- Baby food oatmeal with fruit (42 ppb in composite in summer of 2008): New York City had 82 ppb; Newark had 3 ppb; and Philadelphia had 0 ppb.

Even more disturbing is that, despite confirming the results in the composite samples, FDA could find no records that the individual samples in the highest levels, bologna with 1557 ppb, 1,090 and 686 ppb for collard greens and 686 ppb for salami lunchmeat, were ever tested.

Similarly, the agency could not find any records of the TDS coordinator investigating the possible cause of the high levels of contamination or any communication between the coordinator and others in the Center for Food Science and Applied Nutrition that oversees the TDS. Also not available were the receipts essential to identifying the brand and lot of the samples with unusual high levels of perchlorate; therefore EDF was unable to follow-up.

Conclusion

The agency’s apparent lack of follow-up when faced with jaw-dropping levels of a toxic chemical in food is disturbing. While testing the products is a critical first step, FDA needs to investigate the reasons for the high levels so that it can protect the food supply. Identifying the cause and crafting interventions to reduce or minimize risks, as stated in the TDS purpose statement, is especially important for toxics like perchlorate, where even short exposures during critical life stages may cause lasting harm to a child’s developing brain. But for this to happen, FDA needs to acknowledge the evidence on sources of perchlorate in food, such as its use in packaging or from degraded bleach, and clearly explain what the implications are for the health of children and pregnant women, especially those with low iodine intake.

Update on related perchlorate issue: FDA has not yet responded to EDF’s and eight other public interest organizations’ objection to the agency’s May 4, 2017 decision to reject a petition to ban perchlorate from uses in contact with food. The objection and request for evidentiary hearing were filed on June 4, 2017.

One Comment

How do the perchlorates get into our food? Is it from a specific pesticide? Is it from pollution in the air? Please advise.