The TSCA new chemicals mess: A problem of the chemical industry’s own making

Richard Denison, Ph.D., is a Lead Senior Scientist.

Nary a day goes by without a complaint being lodged by someone in the chemical industry, or in one of the myriad law firms that represent its interests in Washington, D.C., about the delays in EPA’s approval of new chemicals under the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA).

Here’s the irony: Those delays and the general chaos in the TSCA new chemicals program are entirely of the industry’s own making.

As of the middle of the summer of 2017, the program was largely on track. Not surprisingly, there had been a considerable backlog of new chemical cases – a function of a brand new law that imposed significant, immediately effective changes to the new chemical review process, and the need to restart reviews using the new standards for hundreds of cases that had been in the pipeline at the time the new law was passed. As EPA found its feet and brought new staff on board, however, the number of cases under review had been gradually reduced back down to typical levels.

Also not surprisingly, the number of new chemicals being subject to conditions or testing requirements through consent orders had increased relative to the pre-reform review program. That was a direct and appropriate outcome of the increased scrutiny the new law required EPA to pay to potential risks and the sufficiency of health and environmental information on new chemicals during the enhanced review process.

(To briefly summarize the law’s new requirements: Post-reform, TSCA requires EPA to issue an order if a chemical may present an unreasonable risk to health or the environment or if EPA has insufficient information to conduct a reasoned evaluation of the chemical. EPA must then consider whether to issue a “Significant New Use Rule” (SNUR) requiring that any company first notify EPA before deviating from the restrictions in that order so that EPA can review that significant new use.)

Then on August 7, 2017, then EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt announced, in response to relentless pressure from the industry, that EPA would implement sweeping changes to the program designed to hasten the approval process. These changes were actually designed to minimize the restrictions imposed by EPA on new chemicals that might present unreasonable risks or had insufficient health and environmental information.

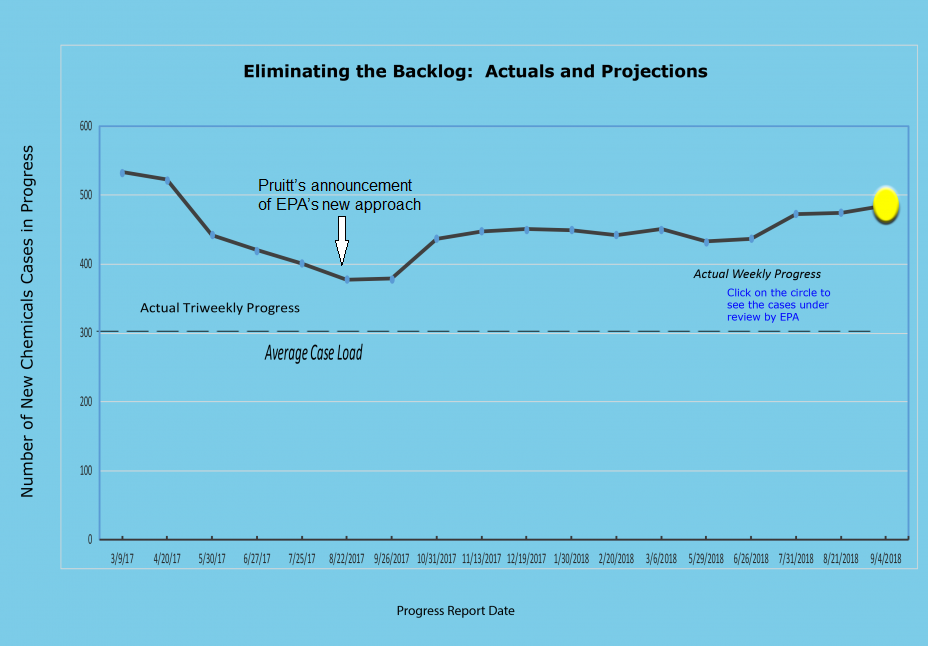

Let’s examine the effects, using EPA’s own data. Below is a chart showing the size of the new chemicals “backlog” taken directly from EPA’s website and current through September 4 of this year. The only modification I have made to that chart is to add an arrow indicating when Pruitt’s announcement was made.

Before that arrow, you can clearly see the steady decline in the backlog down to below 400 cases. At the time, EPA noted that its typical caseload of new chemicals under active review was about 300, and that it had completed and signed consent orders for most of the other 100 cases, which were awaiting company sign-off. Indeed, Pruitt’s own press release declared the backlog had been eliminated.

Now look at what has happened ever since that time: A clear increase in the backlog, with the number of cases under review now standing at close to 500 cases.

The increase is directly traceable to non-stop industry demands for EPA to make unsound, illegal changes to the program.

We want stand-alone SNURs, not orders

Industry’s initial demand was for EPA to stop issuing so many orders for new chemicals. EPA responded in late 2017 with its “new chemicals decision-making framework” – which sought to avoid orders by illegally limiting new chemical reviews only to the “intended” uses of the new chemical producer and relegating any review of other, “reasonably foreseen” uses of the chemical to a later process divorced from the initial review. EPA would generally issue a “not likely to present an unreasonable risk” determination for the chemical based on its constricted review, thereby clearing the chemical for market entry. It would then promulgate a stand-alone “Significant New Use Rule” (SNUR), which would require anyone wanting to use the chemical in a way that differed from the cleared use to first notify EPA, which would trigger a second review of that new use.

While the scheme was fraught with a host of legal, policy, scientific, good government and transparency problems, industry initially welcomed it – not surprising, given the industry had pled with EPA for months to issue such stand-alone SNURs, instead of coupling them with consent orders. But not so fast.

On second thought, we don’t want SNURs either

Not content with this victory, the chemical industry quickly demanded more: a scheme that would eliminate the stand-alone SNURs as well. EPA immediately signaled it was receptive, and this summer began to make yet another “pivot” that deviated even farther from the requirements of the law. The need for even a SNUR would be made to disappear by EPA simply asserting there were no “reasonably foreseen” uses of a new chemical. The first of those decisions was made in late July. Industry promptly endorsed it.

No consent orders, no SNURs – and no testing requirements to boot, because those instruments would have been the means to require (in the case of consent orders) or encourage (in the case of SNURs) companies to fill critical data gaps on their new chemicals.

The actual state of affairs at EPA is difficult to discern at this point, however. Rumors swirl about yet more pivots and even a possible return to the earlier framework.

Denying worker protections

One thing that is constant, however, is the chemical industry’s greed for more. The industry and its allies in the agency now have in their sights additional moves that would allow EPA to shirk its clear obligations under TSCA to address risks to workers – either by asserting that the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) should take care of it, or by shifting the burden of workplace safety off of companies and onto the backs of the workers themselves.

***

Lost in all this maneuvering is the clear purpose behind the enhancements Congress made to TSCA’s new chemicals review program a scant two years ago: The need to better ensure that new chemicals entering commerce are safe for human health and the environment.