Water filters can fight dead zones without hindering farm production

Updated (October 23, 2014): Interior, Agriculture Departments Partner to Measure Conservation Impacts on Water Quality

“Is the water safe?”

In the United States, we take it for granted that the answer to that question is “yes.” But the residents of Toledo, OH, learned recently that their water wasn’t safe to drink for a few days because toxins associated with an algal bloom in Lake Erie had contaminated the city’s water supply. Meanwhile, a Maryland man was released from the hospital after nearly losing his leg and his life to flesh-eating bacteria contracted from swimming in the Chesapeake Bay.

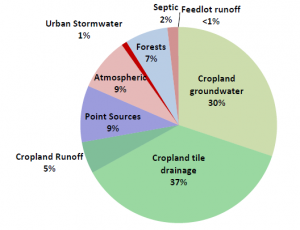

These types of incidents are caused by nutrient pollution. Although nutrient pollution can come from many sources, runoff from agriculture is the dominant contributor to the problem in Lake Erie, the Chesapeake Bay and the Gulf of Mexico. Agriculture-associated nutrient pollution also impacts local streams and lakes, causing fish kills and closing swimming beaches. A recent study in Minnesota suggested that more than 70 percent of nitrogen in state waters comes from cropland.

What needs to be done, and how much will make a difference?

As a scientist, I turned to other scientists to try to answer this question. Using a water-quality model developed by the U.S. Geological Survey, we examined various farm management scenarios to determine what would be needed to reduce nitrogen pollution from the Upper Mississippi and Ohio River Basins by 45 percent – the level of reduction the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency says is needed to shrink the dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico to a manageable size.

Three promising solutions

The results of our analysis will soon be published in the Journal of the American Water Resources Association as a paper titled “Reducing Nitrogen Export from the Corn Belt to the Gulf of Mexico: Agricultural Strategies for Remediating Hypoxia.” Here are the highlights:

- Simply improving fertilizer management on all cropland acres in the region can reduce nitrogen pollution by 12 percent, which gets us almost a third of the way to EPA’s goal.

- Combining improved fertilizer management with cover crops on all cropland acres can reduce nitrogen loss by 30 percent, which gets us two-thirds of the way to the clean water goal.

- Using filter practices that trap and treat nutrients lost from farm fields can get us all the way there without significantly impacting agricultural production. If used alone on 3 percent of the region’s farmland, filters can achieve the 45-percent nitrogen reduction goal. If they are used in combination with improved fertilizer management and cover crops, the goal can be met using less than 1 percent of the region’s farmland.

Types of filters

Clearly, filter practices have a huge role to play in achieving clean water. These practices include innovative wetland designs, such as those promoted by the Iowa Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program, and improved management of drainage ditches.

Filter practices such as wetlands can be implemented on marginal land that contributes little to crop production, especially in wet years when the land may flood anyway. Other practices can be implemented within the footprint of existing ditches and streams without any loss of productive land.

So these practices really provide “the most bang for the buck” in terms of reducing nutrient pollution. But that’s not all they do. In my next post I’ll talk about how these practices can directly benefit the farmer through flood- and drought-proofing.