New research could help resource managers improve the health and resilience of the Mississippi River Basin

Spanning across 31 states, from Minnesota down to the Gulf Coast of Louisiana, the Mississippi River Basin is one of the most significant waterways in the world. Not only is it important for commercial purposes, but it also provides critical wildlife habitat, fresh water and recreational opportunities for communities.

Given the river’s complex alterations and increasing climate impacts, it is more important than ever to take actions that will protect and nurture this treasured basin. Earlier this year, Environmental Defense Fund and co-authors* released new research that may prove beneficial to resource managers, aimed at evaluating and implementing actions to improve the Mississippi River Basin’s overall health and resilience. Based on this research, we are sharing a comprehensive framework that can be used to effectively manage the Mississippi River Basin as part of a whole basin governance structure that includes monitoring, modeling and adaptive management.

First, examine leading indicators of health and resilience

Within our framework, we identified leading indicators that predictively measure improvement towards the Mississippi River Basin’s overall health and resilience. These indicators fit in the following three categories:

1. Reducing stressors: Throughout the Mississippi River Basin, there are a variety of outside stressors that can negatively impact the ecosystem. Broadly speaking, this includes land use changes, river engineering and climate change. Resource managers can take actions that minimize these stressors like removing dams that are no longer useful, implementing levee setbacks instead of building higher levees and increasing natural infrastructure on the agricultural landscape, which help prevent excess nutrients from reaching the river.

2. Enhancing ecosystem function: Basin health can be improved by enhancing its ecosystem function. Functions include hydrologic regulation, energy regulation, biogeochemical regulation, sediment regulation, habitat provision and water temperature regulation.

Many of these functions are provided by forested riparian buffers along stream corridors and by natural land cover like wetlands, forests and prairies distributed throughout the landscape. For example, trees in a riparian buffer shade the water, which regulates the temperature, and they provide woody material in the stream or river to regulate energy. Additionally, they provide habitat for wildlife and prevent sediment and nutrients in runoff from getting into the stream or river, increasing biogeochemical and sediment regulation.

3. Building resilience: Various natural components of the Mississippi River Basin ecosystem can increase its resilience, such as connectivity, physical and biological diversity and temporal variability. Examples where increased connectivity may be beneficial include increasing connections between isolated wetlands and headwater streams and between the mainstem of the Mississippi River and its floodplain. Increased physical and biological diversity would stem from a prairie restoration, which helps improve landscape diversity and attract diversity of wildlife. Meanwhile, an example of temporal variability includes restoring flood pulses within a stream or river.

By utilizing natural infrastructure instead of hard infrastructure, managers can increase the ecosystem’s resilience. For instance, it is possible to reduce flood risk and improve water quality by protecting and restoring riparian buffers, wetlands and floodplains. Grassland restoration also offers these benefits, in addition to sustaining wildlife habitat and supporting carbon sequestration.

Next, determine management actions by comparing with lagging indicators

As resource managers examine the basin’s leading indicators, our framework also recommends looking at lagging indicators. Lagging indicators, such as assessing water quality, measure the current and past conditions of the Mississippi River Basin’s health and resilience.

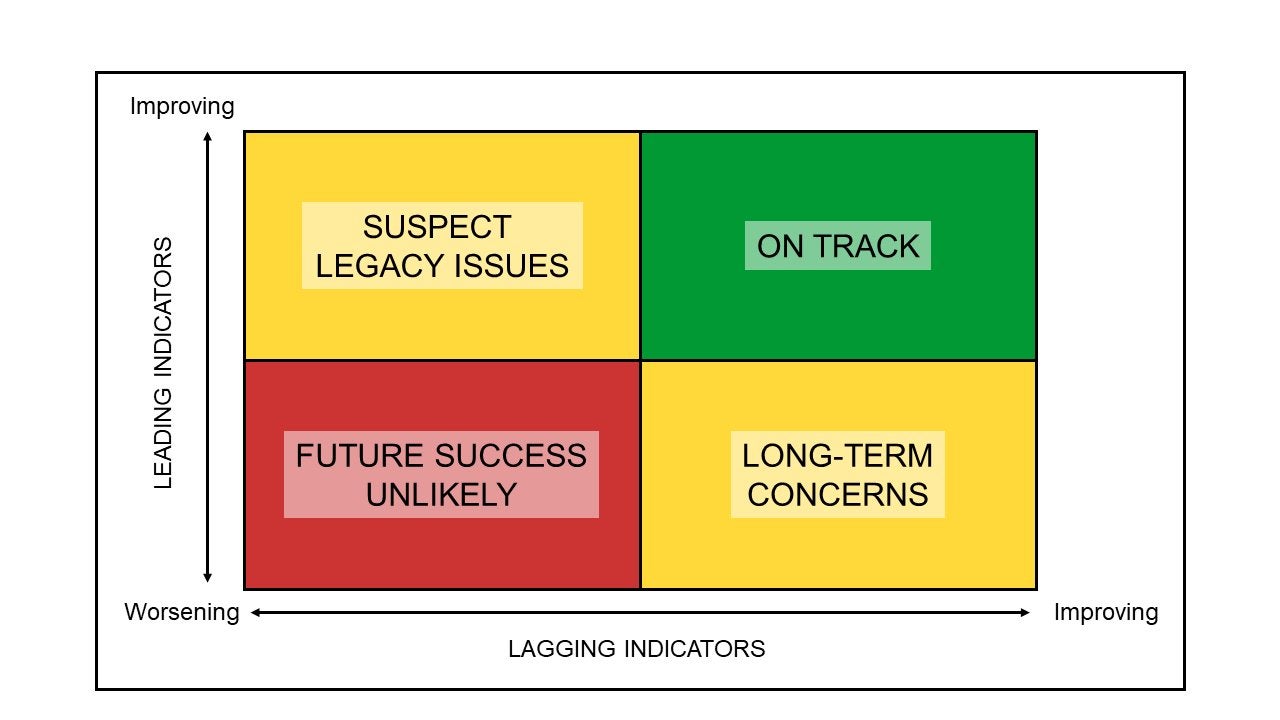

From there, managers can better determine appropriate actions to take. By referencing the chart below, which compares leading and lagging indicators, managers can determine if they are on track to improve ecosystem health and resilience.

The future of the Mississippi River Basin and beyond

The future of the Mississippi River Basin is up to us, and by using this framework, resource managers can improve overall health and resilience, while effectively measuring the success of their actions. This means we can improve cost effectiveness, make it easier for managers to compare projects and promote transparency. Additionally, we will build trust and integrity among managing agencies, so we do not waste resources and support a common governance structure for the basin.

We encourage managers from the Mississippi River Basin and worldwide to use this research, helping our planet’s incredible waterways thrive alongside communities.

Read the full research paper here. Then use our framework to track your progress, in turn, demonstrating the value of federal and state investments in the Mississippi River Basin.

*This research wouldn’t have been possible without our co-authors. This includes colleagues from National Audubon Society, National Wildlife Federation, The Nature Conservancy and Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership, as well as Environmental Protection Agency, United States Geological Survey and various universities.