Shipping’s biofuel moment: lessons from aviation on land use change assessment

By Glenda Chen and Rohemir Ramirez Ballagas

As the global shipping sector races to cut pollution, the fuels chosen today will either accelerate real climate progress or lock in environmental and social harm for decades to come. There are many options on the table to move shipping away from fossil fuels: biofuels from waste and residues, e-fuels powered by renewable electricity and even electrification in some cases. But not all alternative marine fuels are created equal, and getting the regulatory signals right— with strong, science-based social and environmental safeguards— can ensure benefits are shared fairly across businesses, communities, and the environment.

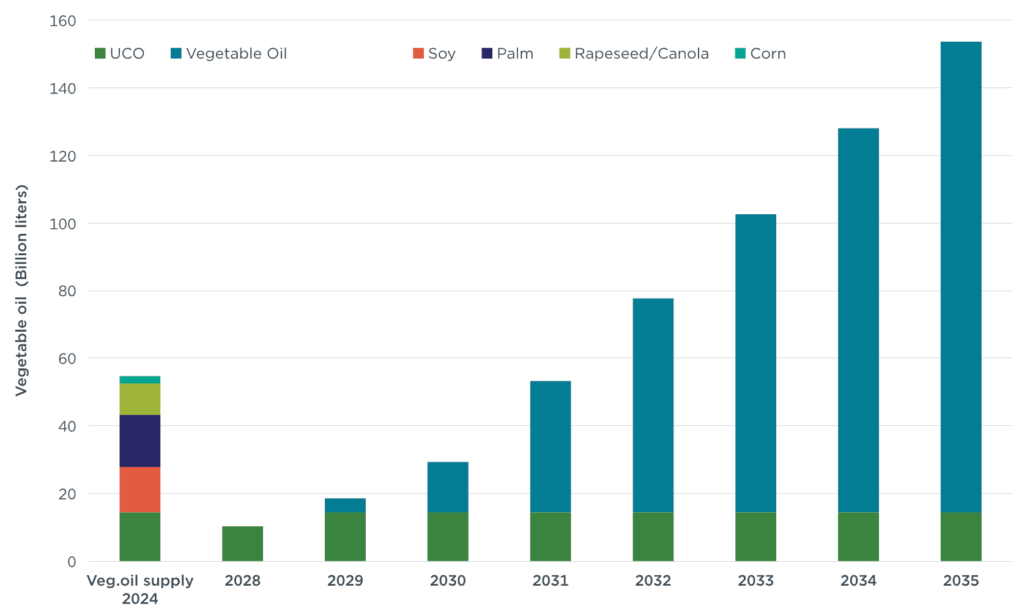

Shipping’s biofuel moment: lessons from aviation on land use change assessment Share on XWithout the proper safeguards, including careful management of their full value chain impacts, even the two main marine biofuel feedstocks— fuels made from vegetable oil and used cooking oil— or hydrogen could deliver little to no climate benefit. They could even, in some cases, cause damage worse than the fossil fuels they are meant to replace. Scaling the wrong alternatives risks unintended consequences including deforestation, food insecurity, and loss of ecosystems. On the other hand, implementing science-based and robust policies that incentivize truly sustainable fuels can help deliver energy security and long-term value for industry and communities.

That’s why the stakes are so high as discussions advance on the continued development of the International Maritime Organization’s lifecycle assessment guidelines.

Member States are facing a critical decision: how to evaluate where alternative marine fuels come from and how they are produced — particularly biofuels, whose popularity is rising as a fast-track option for a transition to low-carbon shipping. Considering the potential magnitude of shipping’s increased demand for limited biomass supplies, the long-term sustainability of biofuels deserves a nuanced approach.

Where the IMO stands & why direct and indirect land use change are important

At the center of this debate is whether and how the IMO will treat land-use change emissions. Get it right, and sustainable biofuels can support the sector’s energy transition, climate progress and local communities. Get it wrong, and the sector could exacerbate negative environmental and social consequences elsewhere.

The latest version of the IMO LCA Guidelines recognizes that land conversion caused by the production of biofuels, be it direct or indirect land-use changes, matter when assessing a fuel’s overall impact. However, these components have not yet been clearly defined, as the IMO is still developing methodological guidance on how to incorporate them. How the IMO defines these terms and sets up safeguards will determine whether an increase in demand for certain biofuels results in deforestation, loss of wetlands, displaced communities and food insecurity. As these can happen through either direct conversion of land to grow bioenergy crops, or indirectly through domino effects, the IMO needs to lay out a credible approach to addressing both direct and indirect land-use changes. Just quantifying these and adding the associated greenhouse gas emissions to the lifecycle emissions estimates is not enough. The IMO needs sustainability safeguards to prevent other impacts on ecosystems and communities – localized non-greenhouse gas effects that cannot simply be traded away on a carbon market.

How LUC is addressed could not only influence whether a particular biofuel’s sourcing, production and delivery genuinely reduce a ship’s greenhouse gas emissions but also whether the sustainability framework distorts fuel choices toward options that undermine shipping’s transition trajectory, delaying meaningful progress and increasing the risk of stranded assets.

Lessons from aviation policy

The good news is that shipping doesn’t have to start from scratch. Ground transport and aviation have already grappled with many of the same questions. The International Civil Aviation Organization has spent years developing safeguards for sustainable fuels built on lessons learned from ground transport policy. Now, it is IMO’s turn to take up the baton and advance it further towards a fully future-proof framework.

In other words, it is crucial for IMO to build on the lessons from both ICAO’s successes and shortcomings when designing its own sustainability framework. One major contextual difference between ICAO’s and IMO’s development of their respective sustainability frameworks is their foundational language as codified. ICAO’s framework prioritizes multidimensional socioeconomic and environmental criteria beyond greenhouse gas emissions, setting a solid expectation of high-integrity sustainable aviation fuel pathways such that state-level incentives channel resources accordingly. IMO’s sustainability framework has the broader policy goal of directly incentivizing the uptake of zero and near-zero emission fuels and technologies, without having yet defined other specific characteristics. This approach requires careful design to ensure that the shipping sector and its broader fuel supply chain invests only in high-integrity sustainable maritime fuels.

ICAO’s sustainability framework includes a sophisticated hybrid approach that combines quantitative and qualitative elements to account for LUC emissions. Under the ICAO framework, certain feedstocks such as wastes, residues and unintended by-products are designated a “zero” LUC value based on qualitative pre-screening. For other pathways involving land-based feedstocks, the induced land use change (including both default direct and indirect emissions) is quantitatively estimated through modeling. Then, for instances involving land use conversion after 2007, the LUC value is compared to the direct LUC emissions to avoid underestimating the overall LUC value. Finally, biofuel producers are then incentivized to implement best land-use management practices, such as yield improvements through cover cropping or cultivation on degraded, unused land, to qualify for a “zero” indirect land use designation.

What shipping can adapt and improve: A hybrid approach between qualitative and quantitative assessment of indirect LUC

Drawing from ICAO’s experience, the IMO should consider the following:

- Apply a hybrid quantitative-qualitative global approach for addressing indirect LUC. The IMO could build on ICAO’s modeling efforts to identify pathways that pose risks to ecosystems and communities and could increase lifecycle emissions. For pathways with high indirect LUC, the IMO should strictly limit or completely avoid their use.

- Adopt a direct LUC methodology to account for emissions impacts caused by direct land-use conversion, building on ICAO’s existing approach.

- Adopt a methodology for mitigating LUC risk with land management practices. Production pathways with any level of indirect LUC risk, even for low-risk feedstocks, should be required to obtain third-party certification demonstrating that this risk has been mitigated through appropriate land-management practices. The shipping sector should focus its efforts to uptake sustainable maritime fuels that do not pose environmental harm.

- To ensure compliance with LUC methodologies and further protect ecosystems, IMO should adopt a fully-fledged sustainability framework, including both a robust set of sustainability criteria and a third-party certification system that is equivalent to ICAO’s. The sustainability criteria should encompass all three pillars of sustainability — environmental, social, and economic — to ensure that alternative maritime fuels contribute rather than jeopardize the United Nation’s sustainable development goals.

ICAO’s SAF framework provides a strong starting point for building a credible, future-proof framework for sustainable marine fuels. As IMO discussions evolve, a fair, science-based approach to direct and indirect land use change can help preserve the organization’s credibility and ensure shipping’s transition to low-carbon fuels is not only fast, but durable — strengthening environmental integrity and delivering positive outcomes for generations to come.