Trump’s EPA may weaken restrictions on disposal of oilfield wastewater — here’s what you need to know

Many Americans are aware that we are experiencing a major energy boom. But what many folks may not realize is that with this increase in oil and gas, also comes an increase in waste – specifically wastewater. In fact, for every barrel of oil produced wells can generate 10 times as much chemical-laden wastewater. All told, the industry produces over 900 billion gallons of wastewater a year, and we know very little about the chemicals in it.

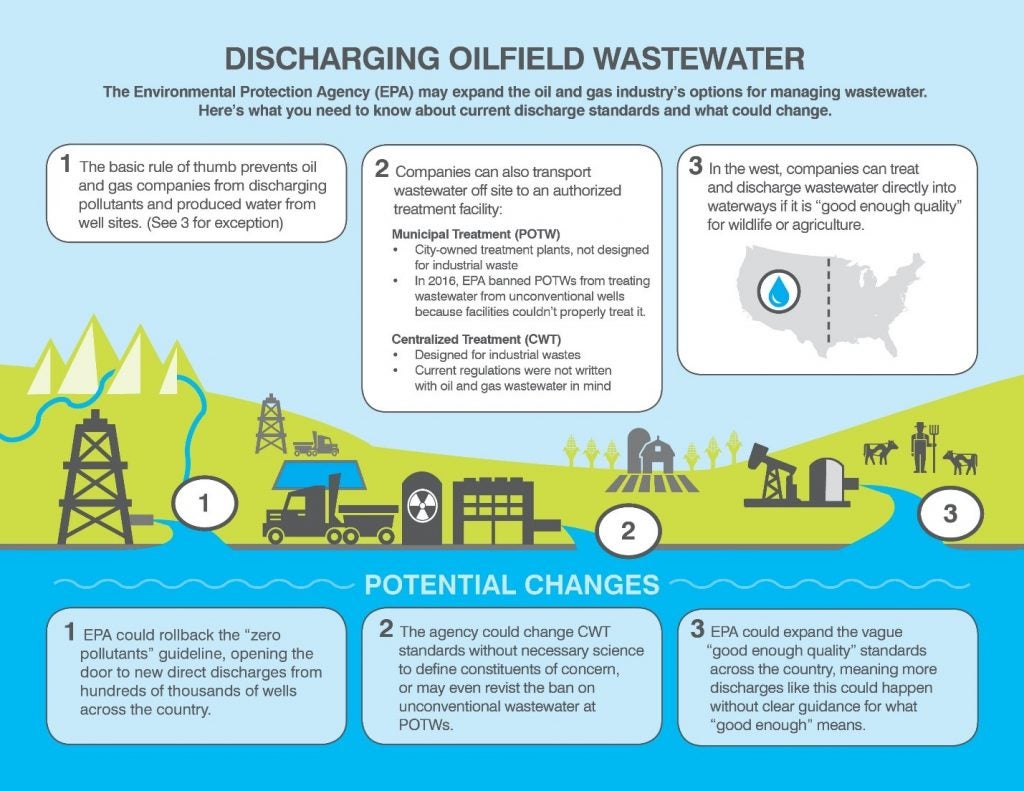

Traditionally, companies have pumped this wastewater deep underground, but the growing volume is creating new challenges– leading many to wonder whether there may be different options for managing or reusing it. One of those options is treatment and discharge to rivers or streams.

Expanding discharge options would be risky though, given all we are still learning about the chemicals in wastewater, potential toxicity, treatability and potential health risks.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) will soon release a study of discharge practices, including the pros and cons of current regulations. States like New Mexico and Oklahoma are also working with EPA to better define their own authorities and options.

As states and EPA consider what a future for produced water discharge might look like– it’s important to know what the standards are today.

Trump's EPA may weaken restrictions on disposal of oilfield wastewater -- here's what you need to know Share on XWhat do the current rules say?

The Clean Water Act requires a permit to discharge pollutants into waterways. The key permitting program — the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) — looks at both the capabilities of treatment technologies as well as water quality objectives in order to determine what kind of permit is appropriate.

Existing options for wastewater discharge

The technology aspect, also known as “effluent limitation guidelines” (ELGs) can vary from industry to industry based on the ability of treatment technologies to remove constituents of concern to acceptable levels. EPA’s study of the technologies and pollutants for an industry results in an ELG that sets the national baseline for discharge permits.

The main ELG for oil and gas facilities sets a baseline of “no discharge” of pollutants into navigable waters of the United States. In 2016, the EPA went further, and prohibited companies who operate “unconventional wells” from disposing of their wastewater into municipal treatment systems, known as Publicly Owned Treatment Works (POTW), since these city-owned facilities are not designed to handle this type of industrial waste.

However, there are some noteworthy exceptions to this rule:

- Any facility in the historically arid west (essentially anything west of Dallas, specifically the 98th meridian line) may discharge wastewater if oil and grease levels are reduced and it is of “good enough quality” for agriculture or wildlife. (Of course, what “good enough quality” really means is up for debate.)

- A well that produces less than 10 barrels of oil a day (also known as a stripper well) also doesn’t have to follow these guidelines.

Outside of this baseline rule for discharges directly from an oil and gas wellsite, there is a second optional route. Operators may also transport their wastewater to what EPA calls a Centralized Waste Treatment Facility (CWT). These facilities can accept and treat industrial wastes that include metals, oil, organics and blended waste streams. However, while the guidelines for these facilities may be more robust than municipal treatment plants, they still weren’t created with the oil and gas industry’s wastewater in mind, meaning that the baseline rules may not currently offer the protections needed to ensure pollutants of concern from oil and gas wastewater don’t reach rivers and streams. (You can learn more about CWTs and the oil and gas industry from EPA’s detailed 2018 study of CWT’s accepting this type of waste, including their own concerns.)

How to define “clean”

The ELG’s are not the final word, though. As a complement to the technology standards, states also have the power to determine how clean they want their water to be by setting their own water quality based guidelines. This allows states to monitor and limit particular pollutants of concern to protect certain qualities or uses of their water bodies. When permit writers are developing a final NPDES permit, they will consider both the baseline technology standard and the water quality standard that applies to the receiving water body and develop requirements based on both standards.

This is important to keep in mind. Even if EPA were to modify the technology standards, states have an opportunity to chime in to address any risks they may see for their water bodies with modifications to their water quality standards.

What might change?

Clean water protections are extremely complicated. And as we learn more about the chemicals used in hydraulic fracturing, as well as the pollutants that may naturally come up from underground, we are also learning our existing standards may be ill suited for the massive volume of chemical-laden wastewater generated in the oilfields.

That’s why it’s so important to keep an eye on what EPA might do to either strengthen or weaken standards for industry’s wastewater. It’s hard to predict what EPA might do, they may:

- rollback the baseline prohibition on discharges from oil and gas well sites,

- allow municipal treatment facilities to handle oilfield wastewater

- extend the vague “good enough quality” standard nationwide,

- or reconsider the standards for CWTs.

What we do know is that there is a lot to be concerned about given limitations in our understanding of the complete range of pollutants that might be in this wastewater – a challenge EPA’s own experts have acknowledged. Permits that allow for the discharge of this wastewater must – definitively – be written to ensure that human health, water resources and ecosystems are protected, and that is going to require work. If anything, these historic rules need to be strengthened, not made weaker.