Texas left in the dust as New Mexico slashes methane intensity on its side of the Permian

By Elizabeth Lieberknecht and Benek Robertson

If you’ve been following the oil and gas industry’s commentary on its methane performance, you might think that the Texas Permian is cleaner than ever. But new measurement data and analysis from the Permian’s Delaware sub-basin show that New Mexico is improving efficiency by capturing more methane while production soars, whereas Texas is maintaining the status quo.

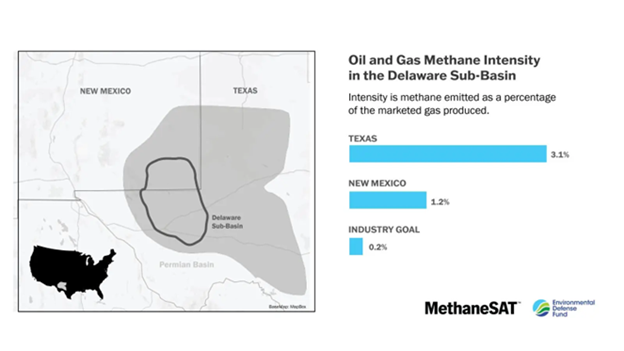

Texas left in the dust as New Mexico slashes methane intensity on its side of the Permian Share on XDrawing on nine satellite overpasses between May 2024 and March 2025, MethaneSAT provides the first robust, measurement-based comparison of methane emissions intensity across the Permian’s Delaware Sub-Basin in New Mexico and Texas — two states that share a resource but allow operations under very different regulatory frameworks.

Texas industry groups hoping to claim credit for their neighbor’s progress should take a closer look. MethaneSAT finds that methane intensity on the New Mexico side of the Delaware sub-basin is half that of Texas, despite New Mexico doubling production since 2020. While New Mexico’s production has surged, the vast majority of the Permian’s methane pollution still comes from the Texas side. MethaneSAT data show that 83 percent of basin-wide emissions — over three million metric tons annually — originate in Texas. In Texas, production has increased modestly — around 20 percent — yet absolute emissions also remained flat, producing no meaningful improvement in intensity.

Portraying Incomplete Data as Mission Accomplished

In recent years, trade groups have used analyses like this recent S&P report (July 2025) in communications about upstream methane intensity — the amount of methane that is released relative to total energy production. That report found positive progress in upstream methane intensity but uses a methodology that omits important emissions data and should be used as an important, but incomplete indicator of methane performance.

Another S&P data analysis, released in October 2025, also reports a decline in absolute emissions. However, these reports both employ measurements from remote sensing technologies that can only detect higher emitting point sources, therefore missing many smaller, dispersed sources that our research shows account for a substantial share of total emissions. Nor do these S&P analyses identify the specific regions that were surveyed. They appear to present oil and gas emissions in New Mexico and Texas together, despite clear regulatory and operational differences across the state line. We need direct measurement-based data for total methane emissions from entire oil and gas basins and sub-basins to be able to make the kinds of claims that industry is touting.

Other papers have corroborated MethaneSAT’s latest findings and illustrate that absolute emissions remain stubbornly high. Varon et al.’s 2025 paper studied the region using weekly satellite observations, finding that total emissions in the Permian region remained flat, and “the decline in methane intensity continues to reflect increasing production, not decreasing emissions.” Despite regional intensity improvements, climate and air pollution from the oil and gas industry remains staggeringly high. Industry should not claim success while continuing to release millions of metric tons of climate super pollutants every year. To remain globally competitive — and to safeguard their employees and neighbors — oil and gas producers and regulators need to better address the industry’s persistent emissions.

Data transparency and scientific rigor matter. Although these S&P reports demonstrate growing remote sensing capabilities in providing methane emissions data, it’s misleading for the Texas industry to claim credit for broad emissions reductions — on either an intensity or on an absolute emissions basis — from data sets that present only a subset of a region’s emissions.

One Producing Basin, Two Vastly Different State Landscapes

New Mexico has adopted a prohibition on routine flaring, a robust leak detection and repair program and nation-leading policies to phase out intentionally polluting equipment. Texas, meanwhile, remains stuck in the past. It routinely allows the wasteful practice of associated gas flaring and functionally exempts smaller wells from basic best management practices like leak detection and repair. Lax and outdated standards for equipment like process controllers fail to address the industry’s second largest source of emissions.

Industry continues to fall short of its own methane-reduction targets. In New Mexico’s Delaware Sub-Basin, methane intensity is still 5 times higher than industry’s own commitments under the Oil and Gas Decarbonization Charter. Texas will need to reduce emissions even more drastically. And the costs of the state’s inaction are only compounding. Texans are already feeling the impacts of our changing climate, including worsening droughts, extreme heat, and catastrophic storms and flooding. Science shows that reducing methane pollution now is the fastest way to slow warming.

The path forward isn’t mysterious. Texas can cut waste, create jobs, and protect communities by following the playbook already working in New Mexico — curb routine flaring, require regular leak inspections and deploy cleaner equipment. New Mexicans are reaping the benefits of regulations requiring more responsible production: an additional $125 million in natural gas captured annually, adding $27 million in royalties and revenue for taxpayers.

Texas policymakers can’t keep allowing industry to point at progress across the border while refusing to clean up their own backyard. The tools, technology and talent are already here — what’s missing is action.