SeafoodNews.com Notes Well Documented Safety Benefits of Bering Sea Crab Rationalization

Heated arguments over fishing policy are nothing new, but evaluating them is harder when they’re based on incorrect information. A recent assertion that safety had not improved under the Alaska crab catch share program badly mischaracterizes the record. While that program is not perfect, safety has improved dramatically. This was the focus of the article below.

By John Sackton – Reprinted with permission from SeafoodNews.com

One of the claims made in Food and Water Watch’s paper attacking catch share programs is that the safety benefit claimed for such programs is illusory.

Unfortunately for them, there is ample documentation and factual testimony to contradict that assertion.

One of the most dramatic results of the Bering Sea crab rationalization program has been a continued improvement in crab fishing vessel safety, which the Coast Guard says could not have been achieved through other methods.

For example, in the five year review of the crab program, completed in Oct of 2010, Jennifer Lincoln of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health and Coast Commander Christopher J. Woodley jointly wrote:

‘The BSAI CR program has clearly demonstrated the ability to improve safety by making foundational changes which increase fishing time, reduce an emphasis on catching power, allow large, more efficient and safer vessels to remain in the fishery, and improve crew experience. These are areas that are typically difficult to control through Coast Guard safety regulations.’

In their paper, Food and Water Watch quotes some crew members from the Bering Sea Crab fishery saying ‘These fishermen generally do not consider the fishery to be any safer, since

owners only hire a minimum number of crew members and have deadlines to meet for processors.’One crew member said: ‘They say it was for security purposes but people still die

every year. The only difference is that there are fewer boats now, so there are less people getting hurt. But they’re doing the same work.’This statement is simply factually untrue. According to the Coast Guard, between 2005 and 2010, there was only a single fatality in the Bering Sea crab fishery. This death was the result of a man overboard. People do not die every year.

In the previous five years prior to rationalization, there were 8 deaths, and in the period from 1995 to 2000, there were 22 deaths.

In fact, during the 1990’s, the Bering sea crab fishery had an ‘astronomical fatality rate of 770 fatalities per 100,000 full time fishermen’, said the Coast Guard.

Whatever other issues may be at stake with the Bering Sea crab rationalization, it is obvious that the program has contributed to improved safety, directly contradicting the claims made by Food and Water Watch.

Further, the NGO goes on to claim that safety is not improved in any catch share fishery whether in the US, Canada, Iceland or New Zealand.

And yet the authors of the paper on which they base this claim say in bold face type:

‘Our results suggest that fishing fatality, injury and illness data should be interpreted with caution and that a meaningful comparison of international data is not possible at this time.’

Once again, the actual data cited does not support the claim being made by Food and Water Watch.

The fundamental question that groups such as this fail to answer is what is their solution for matching fishing capacity with available resources. In their section on the crab fishery, they say ‘The crab fishery lost 177 vessels in the four years following rationalization, causing significant unemployment.’ Yet many of these vessels were only fishing for less than 20 days a year on all crab fisheries.

Further, as is well documented in the Coast Guard reports, the fact that 280 vessels were competing for a small TAC in an olympic fishery put immense pressure on the fleet to add even more capacity to catch their share of the crab.

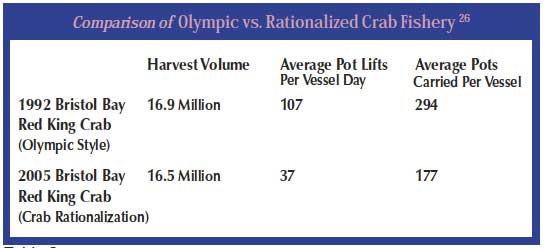

It led to an average pot pull of 107 per day in the red king crab fishery, crews that did not sleep for four days, and overloaded vessels.

With the reduction in the fleet capacity, the average pot pull per day has now gone down to 37. The crews are getting more rest, are better trained, and are operating in a safer environment.

A Coast Guard table makes this point:

Source: Coast Guard Journal of Safety and Security at Sea (Spring 2009)

Overall there are two problems in the US fishery, and globally. One is to allocate access to the resource fairly, and the other is to manage the resource in a sustainable manner. The Food and Water Watch attack on catch shares completely ignores the ‘sustainability’ side of the equation, when they call, by implication, for the retention of 177 additional vessels in the crab fleet to provide employment, and they call for the retention of more vessels in the New England groundfish fleet for the same reason.

Fisheries, like every other business, operates in a market economy that values efficiency. Maximizing employment in a manner destructive to the resource and to the profitability of the industry ends up helping no one.

This type of thinking is behind some of the greatest fisheries failures in history, including the collapse of the cod stocks in Newfoundland, and the collapse of most fish stocks in Europe. The effort to put jobs first, above all other considerations, leads to a collapse in resource, a collapse in employment, and ultimately the end of the fishery.

Catch shares have been put forward as a way to short circuit this downward spiral, and have been largely responsible for those fisheries that have been able to maintain stable employment, stable stocks, and profitable businesses.

Unfortunately for those in the seafood industry who want to ally with Food and Water Watch, that group has no interest in genuinely viable fishery businesses. Instead they have an ideological agenda that will cast fishing businesses aside as soon as they don’t fit the program. They say that ‘Everyone is dependent on shared resources like clean water, safe food and healthy oceans. It’s essential that these shared resources be regulated in the public interest rather than for private gain.’

Although laudable, such sentiments in the real world lead to governments using fish resources for political favors, the destruction of fish stocks, and a global overfishing crisis. ‘Public’ is too often defined as government.

Catch share systems have proven to be an effective tool in balancing the public interest in sustainable resources with the private initiative and entrepreneurial efforts needed to actually bring fish to our tables.