My Arctic Journal

This post is by Fred Krupp, president of the Environmental Defense Fund.

This post is by Fred Krupp, president of the Environmental Defense Fund.

A few weeks ago, I returned from a voyage called the Arctic Expedition for Climate Action. Sponsored by the Aspen Institute, the National Geographic Society, and Lindblad Expeditions, our group [PDF] included over 100 business leaders, scientists, environmentalists, journalists, politicians, religious leaders, and community activists.

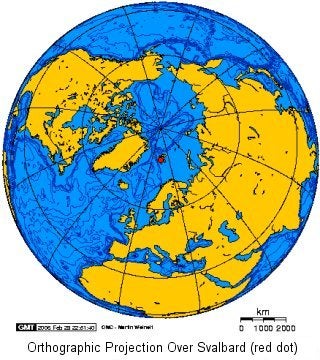

In a word, it was sensational. We set out by ship from Svalbard – almost the closest land to the North Pole, and a three hour plane flight from Oslo, Norway. This is by far the closest to the North Pole I’ve ever been. My prior trips to the north shore of Alaska at Prudhoe Bay and the north coast of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge were much further south.

In a word, it was sensational. We set out by ship from Svalbard – almost the closest land to the North Pole, and a three hour plane flight from Oslo, Norway. This is by far the closest to the North Pole I’ve ever been. My prior trips to the north shore of Alaska at Prudhoe Bay and the north coast of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge were much further south.

There are no trees, bushes, or even grasses on Svalbard – just lichens, mosses, and very low-to-the-ground flowering plants. Plants raise their heads at their peril with Arctic winds and temperatures. We were there at the optimum time for flowering and saw many plants in bloom, including the Svalbard poppy and the compass plant. The top few inches of the tundra are unfrozen in July, though I don’t think temperatures ever reached 40 degrees during our stay. The ground was a wonderful spongy carpet of brilliant colors.

National Geographic took video and photographs non-stop, including video from an unmanned submersible which showed the rich diversity of marine life in the Arctic. One of the guides showed us a particularly striking video clip. Someone took a match to melted permafrost, and it exploded like a blow torch or gas oven. Methane from melting permafrost is contributing dangerously to global warming.

We were treated to several polar bears sightings – some on icebergs near the ship. One, having just gorged on a seal, lay sprawled out with his bear belly hanging off him and onto the ice, in a food coma and seemingly oblivious to the ship’s presence. We spotted as many as 10 polar bears in one sighting.

To hunt for food, polar bears need summer sea ice, which is vanishing. We heard about one starving mother bear who weighed less than 200 pounds at one point. Luckily, when caught and weighed some months later, she was back up to 1000 pounds.

We saw many other animals as well – many caribou (also called reindeer), Atlantic walrus, a very rare sea bird feeding on a dead seal, and cliffs with thousands of sea birds that seemed to all be talking in unison.

The sun never set on our entire exploration, which made for many late night discussions – helped along by a midnight feeding provided by the crew.

On the second day of the trip we toured an old whaling site with gigantic Bowhead whale bones. Bowheads have been all but wiped out in this area by commercial whaling. To me, the bones were a grim reminder that we humans are capable of awful atrocities toward our natural world that impoverish our lives and threaten our own survival.

On another day we hiked with Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter. Jimmy’s perseverance in climbing a hill at age 81 was remarkable, but outdone by our two kayaking outings – especially the second one. On our first outing, the water was filled with icebergs, but it was a lovely, sunny day. The second outing was on an overcast, 32-degree day, kayaking on ice water 200 yards from huge glacier, with frozen wind blowing off the glacier. They are an amazing couple.

While kayaking, my wife Laurie and I passed by an iceberg with bearded seal lying on it. Later a bearded seal swam right up to the kayak. When its large dark eyes looked up into my eyes, I felt a deep desire to be part of efforts to ensure these creatures aren’t decimated by climate change and the other all-too-prevalent threats.