Importing international carbon credits to the EU: How to make it work?

By István Bart and Pedro Martins Barata

Join EDF on Monday, October 20 for the webinar “EU Pathways for International Carbon Credits” on Zoom.

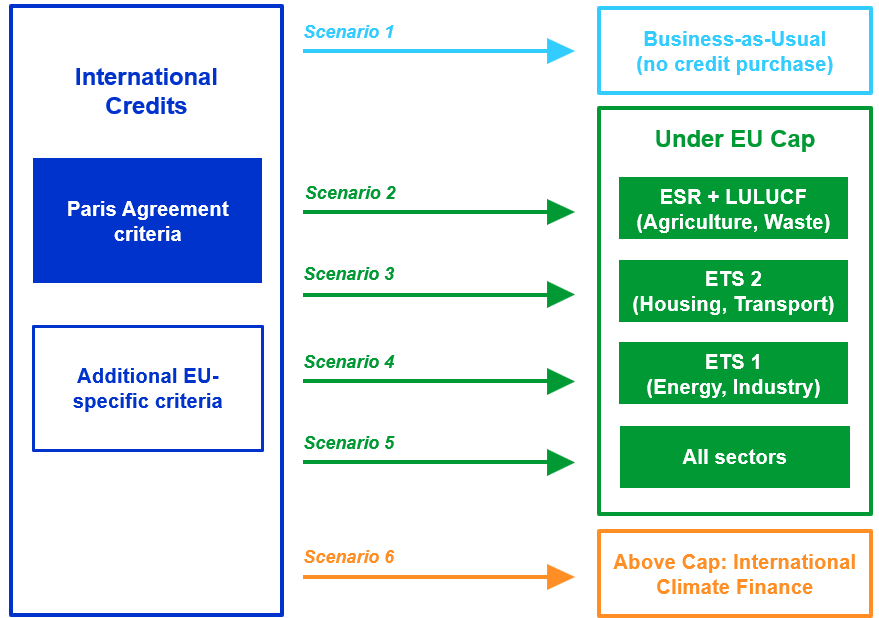

As the European Union sets a new climate goal for 2040, a key question is whether the EU should use carbon credits from outside Europe to help meet that goal. The European Commission’s July 2025 proposal intends to reopen the door to credits for the first time in over a decade. Still, it remains vague on exactly how importing should be done – that is, who should import, how much and where should the imported credits be used? Now is the time to get the design right.

EDF’s latest publication, ‘International Credits in the EU: Strategic Choices & Practical Implementation’, explores these questions. It argues that if done well, importing credits could be a practical way for Europe to keep target compliance costs manageable, protect its climate ambition, and increase its influence in international climate policy. But the details matter – doing it right means we’d need strong rules on quality, clear conditions for if/when credits would be used, and a coordinated EU system to manage purchases and credit use.

Why would the EU consider using international carbon credits?

In the early years of EU climate policy, companies could use credits from the UN’s Clean Development Mechanism (CDM). Over time, concerns about integrity and an oversupplied EU carbon market led Europe to phase that option out. Fast-forward to July 2025: as part of setting a 2040 climate target, the European Commission proposes reopening the door – allowing, from 2036, a limited share of high-quality international credits under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement. The details are still to be confirmed, but the direction is clear: Europe is weighing whether to re-enter the international market as a buyer.

The Commission’s proposal does not spell this out, but there are three reasons why the EU could choose to import credits again:

- Cost containment: Meeting the EU’s proposed 90% climate target by 2040 is neither easy nor cheap, it requires a lot of investment. If these investments are delayed, this could result in higher allowance prices under the EU’s emissions trading scheme or greater burdens in sectors outside it. High prices often create political backlash and thus threaten the feasibility of the climate target. Importing credits is one tool for avoiding high allowance prices or high compliance costs.

- Leverage in international carbon markets: As a large buyer, the EU would be able to set the standards for credit quality – something that would have a global impact on carbon projects worldwide.

- Climate finance: If the EU does not use the purchased credits for its own targets, it could cancel them, thus effectively using the international carbon markets as a form of results-based international climate finance.

Getting it right: What would it look like for the EU to use international credits?

- Quality first: Not all credits are equal. The EU should define a higher integrity bar (additionality, robust MRV, durability, transparency), rather than assuming Article 6 alone guarantees quality. Where helpful, the EU can reference recognized quality labels or ratings like the ICVCM’s Core Carbon Principles label, the Carbon Credit Quality Initiative, or the Tropical Forest Crediting Initiative.

- Buy credits, but don’t pre-commit to using them: No one can know today how many credits the EU will actually need. Instead of setting a big use number up front, the EU could set purchase targets and build a central reserve. That gives the market certainty without committing Europe to automatic use.

- Only use credits under clear conditions: Credits in the reserve should be a safety valve, not a shortcut. The EU would define simple triggers for any release – this could include sustained price spikes or clear evidence a sector is falling behind its trajectory. If those conditions never occur, the EU cancels the credits to be used as climate finance.

- One EU mechanism, not 27 national approaches: Create a Common Credit Management Mechanism to evaluate, purchase, and manage credits across the Union. Centralizing this work avoids duplication, cuts costs, and uses Europe’s scale to shape better global standards.

Next steps for EU decision on credits

The EU’s choices on international credits are still open. Europe’s return the international carbon market is both an opportunity to limit the cost of reducing emissions and a chance to improve the environmental integrity of the carbon markets globally – but only if the right quality criteria are set and implemented.

Join EDF on Monday, October 20 for the webinar, “EU Pathways for International Carbon Credits” on Zoom.