An obvious solution for building electric transmission faster: Use railroads and highways

The U.S. needs to build a lot more high-voltage electric transmission lines. Our current system is disconnected in all of the wrong places, leaving bountiful renewable resources stranded, individual regions isolated, and disadvantaged communities with unreliable power and exorbitant costs. Even where we do have connections, many of the lines are outdated and can’t accommodate all of the energy that is being produced.

To ensure that our grid is resilient to severe storms and heat, capable of meeting our climate goals, and can deliver energy at reasonable cost, we will need to build or upgrade around 75,000 miles of transmission lines – the equivalent of building 30 transmission lines connecting Los Angeles to New York City.

Historically, building transmission lines over long distances has been an arduous and time-consuming process. Many lines have taken decades to reach completion, while others don’t even make it to the construction phase. Since transmission lines typically pass through many separate state and local governments, transmission developers are required to apply for a permit with each of the individual states, and potentially the individual municipality that it crosses. Each of these state and local processes can take years, leading to potentially cascading timelines, particularly for longer distance projects. And of course, any of these permitting bodies could simply deny the project from being sited in their state or local jurisdiction, setting off further actions and delays that a transmission developer will need to respond to, if they don’t simply throw in the towel.

But there is a small exception to this sluggish process: a transmission line that is being built within a specific Department of Energy (DOE) designated “corridor” and that did not receive a construction permit from a state or local agency within one year of filing their application may seek a federal permit from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) to move forward with their project.

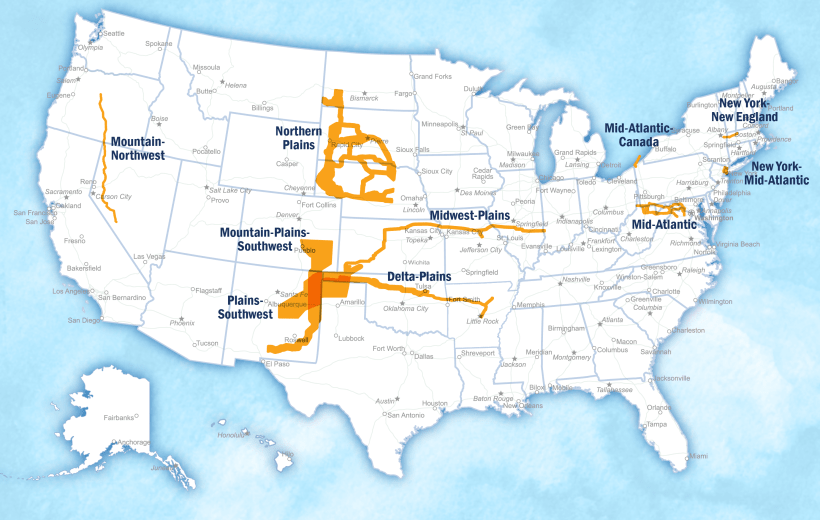

In May, DOE proposed 10 National Interest Electric Transmission Corridors (NIETCs, pronounced Nit-Sees). These NIETCs represent areas where DOE has found that new interstate transmission could provide outsized benefits to consumers affected by high electricity costs and reliability concerns. Transmission lines built in these corridors will become eligible for additional financial support under the Inflation Reduction Act and Bipartisan Infrastructure Law. These proposed designations represent a necessary step forward in the process of getting more transmission lines in the ground. However, whether these corridors can deliver on their promise of removing barriers to building new transmission projects depends on where the boundaries are drawn, and whether they include the range of reasonable alternative routes that a developer may need to consider.

An analysis commissioned by EDF found that the boundaries of the corridors were drawn far too narrow, unnecessarily excluding existing infrastructure corridors and their rights-of-way — such as highway and railway routes — that can create more pathways for delivering reliable and affordable power.

Background: What are rights-of-way and why do they matter for electric power?

Highways, railways, transmission lines and pipelines each operate on what is known as a “right-of-way.” Linear rights-of-way have their roots in 19th century federal land grants to encourage railroad development across the country. As the U.S. developed more infrastructure in the following years, federal and state governments earmarked millions of miles of linear tracts to build roads, highways, pipelines and power lines – forming a network of routes that move between population centers, natural resources and other points of interest.

Rights-of-way don’t have a universal shape or size. The width of a right-of-way largely depends on the type of infrastructure it is hosting (rail, highway, utility line etc.) and can range from a dozen feet to several hundreds of feet. While some overhead transmission lines may have sizeable width requirements for their footprints and clearances, buried transmission lines can be built in far narrower footprints, potentially enabling transmission lines to be built in narrower existing rights-of-way.

The effort today to co-locate transmission around the country

While it may appear obvious to look at ways to consolidate our public infrastructure, co-locating electricity with other linear development has not been a policy focus until somewhat recently. This is surprising given that co-location of broadband internet lines with rail had been relatively commonplace throughout the 1980’s and 1990’s. Co-locating transmission lines with other infrastructure did not arouse much attention until 2003, when policymakers in Wisconsin took up the issue and passed a first-in-the-nation law that required electric utilities to look at siting new transmission lines within existing transmission and transportation rights-of-way before considering other locations. Other states are finally catching up to Wisconsin, with Minnesota recently passing a bill that would open all rights-of-way corridors to host transmission lines.

At the federal level, efforts have been far more complicated. Although Congress first gave the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission — an independent agency that regulates the interstate transmission of electricity — the authority to permit interstate transmission in high-need areas in 2005, it was effectively blocked until the passage of the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law in 2021 (16 years later) which cleared the previous legal hurdles. That process finally got underway last year when the DOE published its 2023 Transmission Needs Study.

The Federal Power Act requires that after DOE completes a Transmission Needs Study that it designates areas as NIETCs if the areas, based on the Needs Study and other relevant sources, are found to have or are expected to experience significant transmission congestion or constraints that affect their ability to deliver power.

In issuing its preliminary list of NIETCs, DOE made the decision to draw NIETC boundaries narrowly primarily to reflect areas where transmission developers are planning to build transmission lines. However, a transmission developer’s planned transmission route isn’t always where the line will end up being sited. A series of factors, including stakeholder input can impact a transmission line’s final route. As a result, NIETCs should be drawn to reflect all of the places where a transmission line could reasonably get built, especially areas where siting transmission will minimize impacts.

Since rights-of-way are often clear of natural resources and residential or commercial structures, co-locating a new transmission line on an existing right-of-way could limit the potential impacts of a project by reducing the need to remove trees, dredge wetlands, enter species habitats, and build on private land or near to residential neighborhoods. It could also speed up the development of the project. A transmission line built on an existing right-of-way would likely have fewer individual landowners to engage with, as large sections could be controlled by a single entity.

It is therefore no accident that Congress amended the Federal Power Act to direct DOE to consider maximizing existing rights-of-way when determining the bounds of a corridor.

Our analysis reveals transmission opportunities in plain “site”

While DOE conclusively states in its guidance document that many of the NIETCs “would maximize the use of existing rights of way including utility and highway rights-of-way”, the agency glaringly leaves out an obvious and often used category: railroads. Spurred by this omission, EDF worked with Horizon Climate Group to compare the preliminary NIETCs against the locations of the dominant infrastructure categories—highway, railroad and utility infrastructure—to determine whether any of those existing rights-of-way were near to and running parallel to the corridors and should have been included in the designation. Our results revealed an extensive network of existing rights-of-ways near to or parallel to the NIETCs, only a small portion of which were included in DOE’s proposal.

Here are two of the corridors that could be expanded using more rights-of-way, according to our analysis:

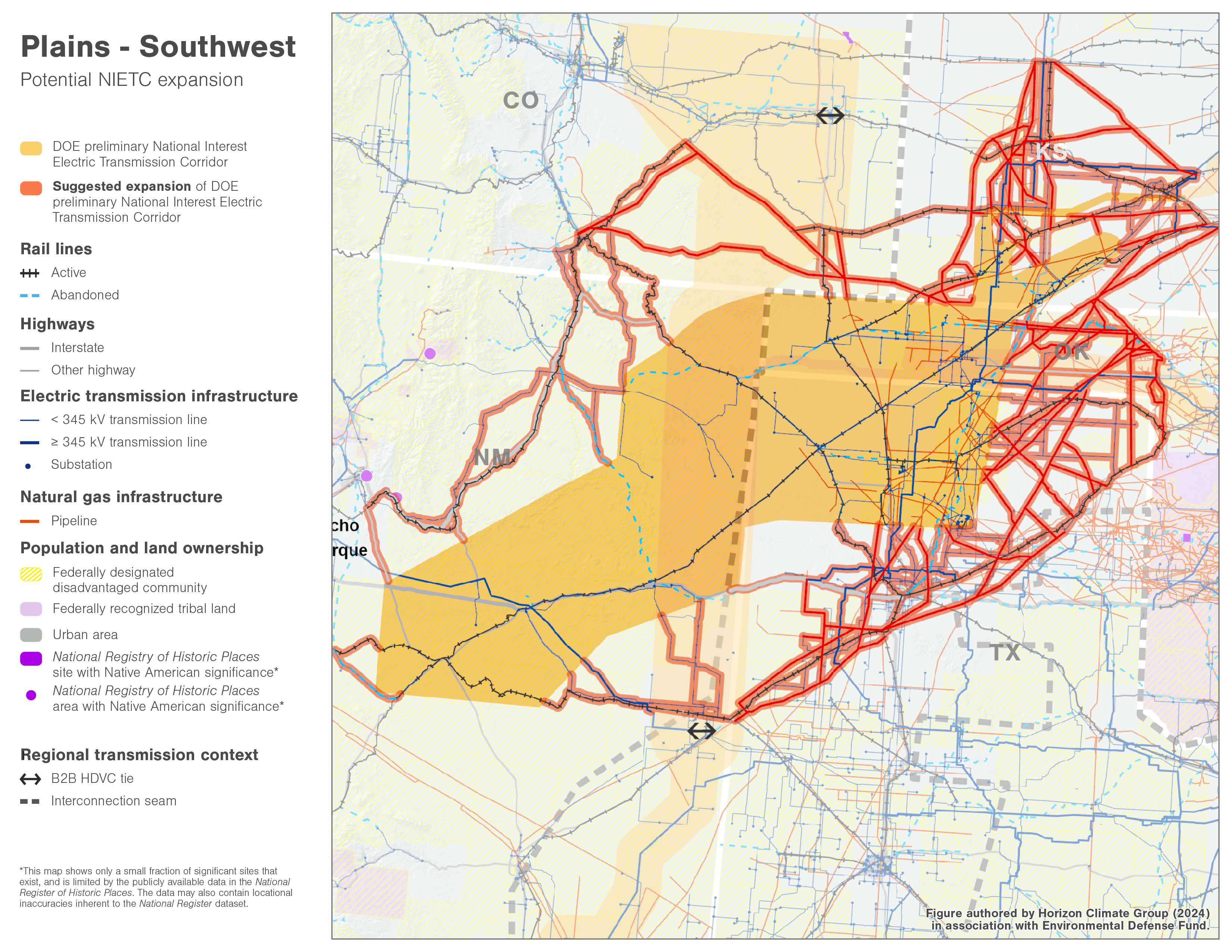

Plains-Southwest

DOE’s proposed Plains-Southwest NIETC (orange highlight on the map):

- The DOE’s proposed Plains-Southwest NIETC does not follow one specific proposed transmission line or an existing right-of-way. As a result, the shape of the NIETC is far wider than others.

- This NIETC is intended to address the anemic transmission infrastructure in parts of New Mexico, Texas and Oklahoma, and to a lesser extent, Kansas, to increase connections between the mostly disconnected eastern and western interconnects (that split their energy systems almost exactly right through the middle of the country) and the majority of Texas, as well as between several individual transmission planning regions, which have been somewhat siloed in building transmission between regions.

- As the proposed Plains-Southwest NIETC is widely drawn it does include some existing rights-of-way; notably, DOE’s map includes a stretch of highway that runs from the corridor’s most northeastern point in Kansas, with its most southwestern point in New Mexico.

What our analysis found (red highlight on the map):

- Our analysis, however, found that the rendering of the NIETC that DOE proposed unnecessarily excludes additional existing rights-of-way that are near to the NIETC that could provide additional east-west and north-south sites for co-locating transmission lines. While this is particularly true with the infrastructure-rich eastern part of the NIETC—between Texas, Oklahoma and Kansas—there are also several long running rights-of-way in the western section of the NIETC in New Mexico and Crossing over into Colorado.

- Our recommendations to DOE therefore reflect the inclusion of these areas in the final NIETC which would better ensure that the agency maximized rights-of-way, consistent with the law, and provide developers with the opportunity to build transmission within a NIETC that could be sited in a lesser impactful area.

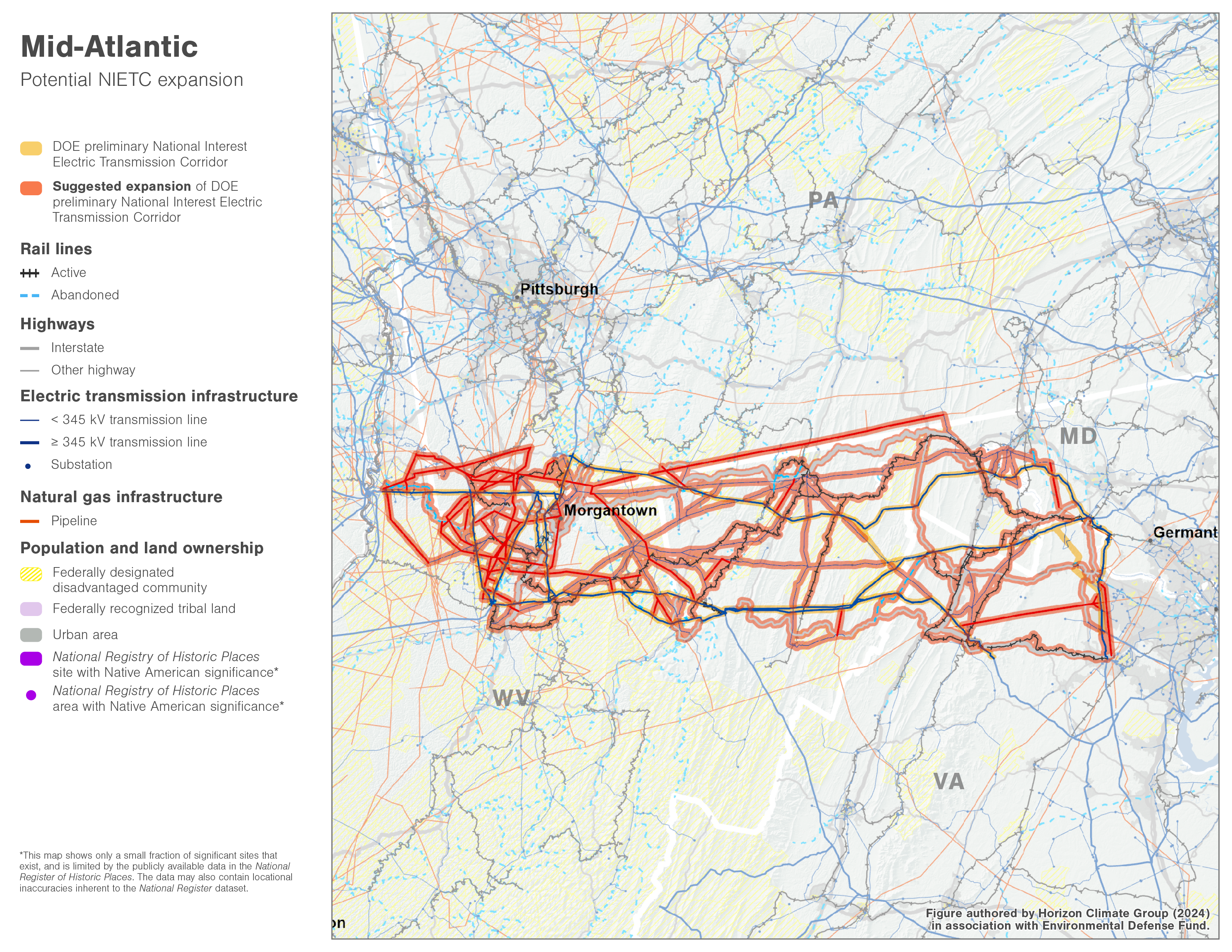

Mid-Atlantic

DOE’s proposed Mid-Atlantic NIETC (orange highlight on the map):

- DOE’s proposed Mid-Atlantic NIETC is a series of parallel sections, intersections and tributaries two miles wide that travels between parts of Maryland and Virginia just outside of Washington, D.C., extending further into western Virginia and Maryland and Pennsylvania, before ending in West Virginia.

- The purpose of the line is to increase capacity within the region to address load growth, planned fossil generation retirements, and to ensure that renewable resources can reach retail customers.

- Most of the NIETC is drawn to follow existing 500 kV transmission lines that could host an additional transmission line within its existing right-of-way.

What our analysis found (red highlight on the map):

- There are additional transmission lines nearby, running parallel and intersecting the NIETC that DOE failed to include.

- DOE also failed to include any nearby highway, railway or fossil fuel pipeline rights-of-way within the NIETC.

- Comparing DOE’s proposed NIETC against the map of other existing rights-of-way revealed that there are ample opportunities where the Mid-Atlantic NIETC could be expanded to include hundreds of miles of additional existing rights-of-way that are near to and running adjacent to the proposed corridor.

- Adopting EDF’s recommended NIETC revision would better ensure that DOE complies with the Federal Power Act, and “maximizes existing rights-of-way.”

Based on these findings, EDF and partners have urged DOE to expand the boundaries of the NIETCs to better ensure that we get more transmission built in places where it is needed and where it causes the least impact to communities and the environment. Including more potential pathways is critical to connecting and delivering reliable, affordable and clean power to the communities that need it most. We will continue to work with DOE on the next phase of its NIETC designation process this Fall to ensure that the final NIETC designations are as effective as possible.

EDF’s comments to the Department of Energy can be found here, and the Geospatial Imaging System data can be downloaded here.

One Comment

Hi, thank you for this information. I am not a business person, engineer or scientist. The pictured NIETC map of “corridor” routes, that will cross the US to carry solar power “interregional” distances, with utility scale high voltage lines, very high towers, stations and many storages appears unproblematic, more than economical for developers, especially if the corridors do match up with already established RoWs.

For decades, ideas of using – all – already biologically disrupted ecosystems for expanding and bulking up energy corporations’ Grid, sounded very good: Avoided damage to the “free work and services” of irreproducible, irrecoverable, irretrievable natural wildlands. And, as evolution of profitable solar tech and engineering gains momentum, the quickly built out tech and engineering of yesterday and today – on already compromised lands, would be more easily removed as it becomes less productive, less profitable for its investors, in comparison to the growing “micro utility” localized, customized grids and businesses.

The map doesn’t show the enormous areas of “cheap, sunny, flat enough” space (Last Stand natural desert wildlands) needed, for building oldstyle commercial corporate utility scale solar energy “large array” infrastructure. I am hoping there will be delays in permitting that work. No other concept for the localized, compact, modular, configurable in-town, on-site use grids, that all neighborhoods, towns and cities would want for their respective homes, businesses and industries – could be as programming-safe, reliable, and reliably affordable into the future – as the adaptable micro utility.

No part of the Mojave Desert was or is “free”, “unlimited” “wasteland”.

We all look forward to life with solar power, just not done anymore “The Only Way! It Can Work!” —

— For commercial corporate utility scale infrastructure developers.