The environmental integrity of emissions reductions depends on scale and systemic changes, not on sector of origin of the emissions

We urgently need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions far beyond current climate pledges, even if these were fully attained. But there’s a completely doable way to make major progress, near to hand.

Natural climate solutions can provide 20% of all the emissions reductions we need by 2050 to keep average global warming under 2 C. Stopping tropical deforestation, allowing tropical forests to regenerate and restoring degraded lands are the most important methods, particularly in the next decade. Letting countries or companies that exceed ambitious targets trade their surplus emissions reductions to those who fall short would permit much greater global emissions reductions than not trading. Countries could reach their targets more quickly, and trading would create more incentive to protect and restore land.

Some researchers and policy makers have held that nature-based solutions, such as stopping deforestation, are too risky. A forest you protect today could burn down tomorrow. But in fact, this problem exists with all emissions reductions, not only those based in terrestrial carbon. And nature-based solutions are worth considering as many of the highest quality and highest value emissions reductions that are feasible in the coming years.

A new article in Environmental Research Letters by scientists and economists from the Environmental Defense Fund and Princeton University shows that the best way to execute emissions reductions – whether they are from protecting forests or cutting down on fossil fuel –is to go big.

Scale is key

Emissions reductions that are truly effective need to:

- Ensure real impact from policy and actions (additionality).

- Avoid leakage, or the problem of having lowered emissions reductions in one place causing increases somewhere else.

- Make sure that reductions last over time, so that reductions at one point in time aren’t cancelled by increases at a later point in time (permanence).

The scale of reductions and whether they involve systemic change is the key indicator of their environmental integrity. It’s easy to replace one solar energy plant with a coal-fired plant, but if a whole country or large region shifts from coal to solar, it’s much harder to go back. Mines are closed, infrastructure, such as railroad handling capacity, is retired.

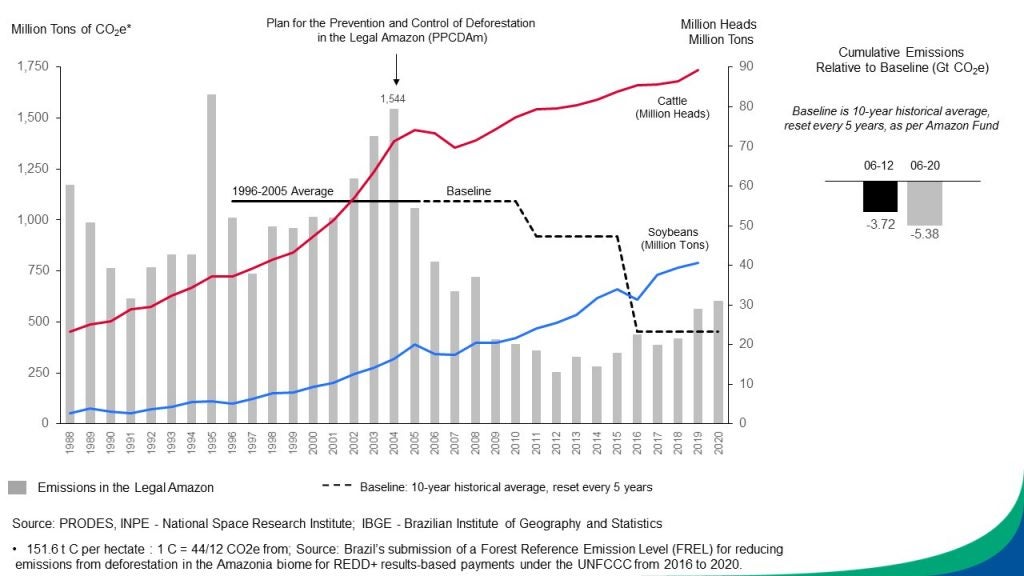

We can see the role of scale and systemic change clearly in the real world in Brazil’s emissions reductions from Amazon deforestation from 2004 – 2012.

Brazil reduced Amazon deforestation by about 80% between 2004 and 2012, while increasing cattle and soy production (as well as GDP and GDP per capita), largely owing to improved deforestation monitoring and transparency, ramped-up law enforcement, and recognition of Indigenous territories and creation of protected areas.

Holding firm

The scale of these efforts has been key to pushing back on steady attacks on forest protection. Starting in 2012, government and the agriculture caucus of the Brazilian Congress have steadily eroded environmental regulations and defunded enforcement. Since 2018, with the election of extreme right-wing Jair Bolsonaro (“Brazil’s Trump”) as president, the aggressively anti-environmental, anti-Indigenous government has accelerated the assault on the forest and Indigenous territories.

Media coverage since 2012 leaves the impression that Brazil had previously reduced deforestation, but has since undone the gains. In reality, reductions in deforestation have proved remarkably robust. From 2006 to 2020, Brazil reduced emissions from Amazon deforestation more than five gigatons – in spite of post-2012 increases and drastically curtailed law enforcement.

The previous era’s large-scale policy changes, plus changed agriculture practices that accompanied it, as well as widespread public support for stopping deforestation and media coverage meant that underlying economic demand for commodities such as beef and soy, previously powerful drivers of deforestation in Brazil, was met with much less deforestation. These kinds of changes, over the whole Amazon, for over a decade, have proven quite difficult to undo.

The big win

The Brazil case shows the effectiveness of going big to meet the requirements of additionality, permanence, and avoiding leakage for emissions reduction.

During Climate Week, the Global Landscapes Forum’s Amazonia Conference is hosting an event to showcase how organizations representing Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities, NGOs and public-private initiatives have been working for years to scale up forest protection. Some of the effects of their work are highlighted in our Environmental Research Letters paper. But importantly, they show that scaled up tropical forest protection can’t be done without successful, equitable and inclusive forest partnerships to ensure long term systemic change and emissions reductions.

Recently launched initiatives like the LEAF (Lowering Emissions through Accelerated Forest Finance) Coalition and the Green Gigaton Challenge are looking to build on Brazil’s successes and learnings to protect tropical forests globally by driving public and private sector funding toward large scale programs to protect tropical forests.

These initiatives are proving the point that making reductions at scale – geographically and over time – is the best way to ensure environmental and social integrity.