What Will it Cost to Protect Ourselves from Global Warming?

This post is by Nat Keohane, Ph.D., Director of Economic Policy and Analysis at Environmental Defense Fund.

This post is by Nat Keohane, Ph.D., Director of Economic Policy and Analysis at Environmental Defense Fund.

We just released a new report on how climate change legislation will impact the economy [PDF]. There have been many recent cost estimates, but ours provides something unique. To put the numbers in perspective, we looked at model projections in the context of government data on jobs, consumer expenditures, electricity consumption, and so on.

The models – all from highly respected, independent sources – don’t agree on much. But they do agree on one thing: the overall impact on the economy will be very small. All the models project that, over the next twenty years, the cost of climate policy will be just a few months of economic growth.

The good news coming out of this study is that we can afford ambitious cuts in global warming pollution.

The Models We Analyzed

We looked at five models: one run by Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), two by Department of Energy (DOE), and two contracted by Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). These represent all the models we could find that:

- Looked at impacts on the U.S. economy,

- Considered policies along the lines of the Lieberman-Warner Climate Security Act, and

- Came from highly respected, independent sources willing to make their results and assumptions completely transparent.

Note that these models look only at the costs of reducing emissions. They don’t consider the costs of inaction – that is, the damages that will result from unchecked global warming.

What We Found

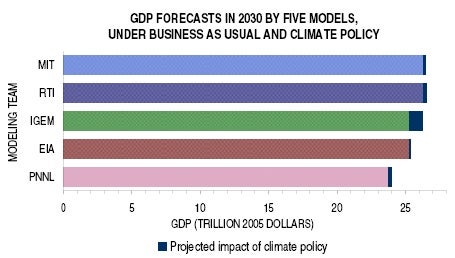

The cost to the U.S. economy will be miniscule. The median estimate is that ambitious climate policy will reduce annual economic growth by only three-hundredths of a percent (0.03 percent). Over the period 2010 to 2030, the models estimate a reduction of just one-half of one percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Compare this to projected economic growth over the same twenty year period of 70 percent.

Why do other reports say the costs will be high? Two reasons:

- Our opponents tend to cherry-pick the numbers, choosing the highest ones they can find.

- They present the numbers out of context. The U.S. economy is so huge that even a tiny estimate in terms of percentage is enormous in terms of dollars.

Here’s another way to put the cost in perspective. The models differ by as much as 10 percent in their predictions of business-as-usual output in the year 2030 because the drivers of economic growth are themselves uncertain. This difference in estimates is 17 times the projected cost of a cap on greenhouse gas emissions. In a real sense, the impact of climate policy is in the margin of error of these models!

We can afford an ambitious cap-and-trade program.

- The number of manufacturing jobs created and destroyed every three months is substantially higher than the number projected to be lost over 20 years due to an emissions cap.

- The impact on household consumption will be minimal – less than a penny per dollar of income for the average American family.

- The largest impact will be on household energy bills, but even that will be modest – just a few dollars a month higher.

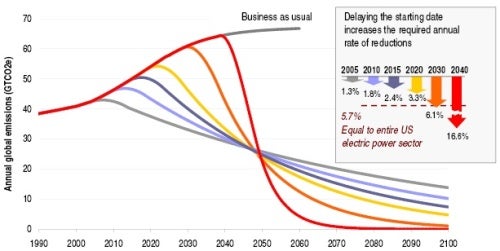

The cost of inaction is higher than the cost of an ambitious cap-and-trade program. Delay risks irreversible climate change. The longer we wait, the steeper emissions cuts must be to keep warming less than 2°C above preindustrial times – the threshold scientists tell us risks catastrophic consequences.

As the graph below shows, the cost of waiting increases quickly:

- Waiting until 2030 would require annual cuts of over 6 percent per year – more than the contribution of the entire U.S. electric power sector. Cuts of this magnitude would be extremely expensive, and may not even be feasible.

- Waiting until 2040 would require annual cuts of nearly 17 percent per year to avoid catastrophic climate change – almost surely impossible.

A wise climate policy provides the foundation for long-term economic prosperity. A look back at America’s economy over the past century shows that we have led the way in each major economic revolution, from mass production to semiconductors to the internet. Technological leadership drives our economy. A cap on carbon will spark innovation and allow American entrepreneurs to lead the world in the coming low-carbon economy.

For all the numbers and details on our methology, take a look at the full report [PDF].

6 Comments

I’ve read the full report, and it was very useful to me. I’m busy checking out the references, but maybe you can help a poor non-economist understand something:

1) It’s really nice to see the use of a set of models to bring out the variance. But, underneath them all appears to be a total GDP CAGR of roughly 3%. Where does that come from, or more specifically, how much is from Total Factor Productivity / Solow Residual or equivalent? And can you point at a good explanation of that to ease my mind that that’s believable? I think it is the mainstream economics view. Yes?

2) Here’s my concern: I’ve been looking at the work of various “biophysical economists” (or whatever they’re called, i.e., like Charles hall, or Robert Ayres+Benjamin Warr. I look at their models, which analyze GDP growth by adding an energy input (or productive work = efficiency * exergy), and get awfully good fits for the residual, with some boost in last few decades, probably from computing.

They argue that the multiplier effect of energy is way more than the percentage actually spent, and I understand that energy intensity has improved (although I’m not sure how much of that is offshoring of manufacturing).

Their math at least looks reasonable, and the general idea makes sense to me (but I am not an economist).

As an old farmboy, I do note that farmers with tractors+fuel and electricity are richer than ones with only draught animals, and those are usually better off than those with none.

3) Meanwhile, we are either already at Peak Oil, or it’s coming in next few years, and Peak Gas looks to be a decade or two later. Given that these two provide ~65% of the energy in the US, we will have a dip from the energy from such fuels. Given that some of us (like CA) use a lot of energy (19% of our electricity) to pump water, and that nitrogen fertilizer is made with natural gas, and farm machinery runs on petroleum, none of these seem likely to get cheaper.

4) If these folks’ models are better approximations to reality, and we’ll know within a decade, I think:

If the US goes *all-out* on efficiency and building sustainable power systems, MAYBE we can avoid GDP-flattening and downturn. Ayres has examples of different cases based on efficiency, and only the most aggressive efficiency effort manages to get numbers like those you have. The other others are ugly.

5) I think this means that rather than efficiency+rework being something we *can* afford at modest cost, they are things we cannot afford to do without, i.e., it is even more urgent. The Hirsch report thought we really needed to start 20 years before peak Oil.

Anyway, help me out on the economics:

a) The mainstream says 3% growth, with no mention of Peak Oil&Gas, i.,e.., business as usual as it has been for the last 100 years or so, as we’ve used more energy, and raised efficiency.

b) A small minority says that GDP growth is strongly affected by productive work/energy, and that we have really hard work to do over the next few decades just to stay even. These folks seem credible, as do two friends who were Chairman or Vice-Chairman of two different major oil companies.

Please let me know if I’m missing something, as I’d much rather believe 3% growth rates with no impact from Peak Oil&Gas

I forwarded your message to Nat – waiting to hear back from him. He may be out of town.

Nat’s traveling all week, but he’ll be able to respond next week.

Thanks, that’s fine … the general topic of “climate & economy” won’t go away any time soon.

Hi John,

Thanks for your feedback and questions!

Yes, the growth rates in these models are in the range of 2.5-3% per year. Note that US GDP has grown at roughly 3% per year or slightly more over the postwar period, so these projections reflect the consensus view that growth will be slightly lower over the next fifty years than over the last fifty years.

These models all project growth by essentially plugging in some autonomous productivity improvement, along with projections for growth in labor (from population growth) and capital (from the assumed savings rates). Energy intensity is taken into account explicitly in these models through the sectoral production functions. What these models do not do is to model endogenous technical change — i.e., how investment in R&D for energy efficiency (or pollution abatement) technology responds to a carbon price.

It is true that the projections of BAU energy prices, esp. oil and gas, are crucial and also vary widely. Most of these models rely on the Energy Information Administration’s Annual Energy Outlook, even though that is widely viewed as exceptionally optimistic (e.g. oil and gas prices fall back to recent historical averages, well below their current levels, and then stay there.)

That is just one reason why in the report we emphasize the importance of focusing on what the models say about the impact and design of climate policy rather than the absolute forecasts — which we know are going to be wrong.

It is certainly true that all these models project major investments in decarbonizing the energy infrastructure — there’s no getting around that. But of course those investments show up as increases to GDP. The point is not that this will be easy, but that if we start now it will be affordable.

That’s largely a framing question; the intent of the report was to take off the table the notion that “climate policy will bankrupt the US economy,” while acknowledging that this is an urgent and very difficult challenge.

Again, we are going with the judgment of the best mainstream economists out there who are doing this sort of modeling. I think there is broad consensus that annual growth of 2.5%-3% is a reasonable expectation over the long term, and I see little to undermine that view. And while I think there is a fair possibility that oil prices in particular will remain high, due to skyrocketing demand from China and India and sluggish supply-side response, that is different than saying that absolute oil production will decline (as in the Peak Oil hypothesis). Sure, oil will probably be more expensive, but I don’t think there’s sufficient reason to think that that will fundamentally erode productivity over the next several decades. The US economy is pretty robust — that’s the main takeaway point of our report, after all.

Nat: thanks.

1) That’s a good summary of the mainstream predictions, and I absolutely agree that if we keep to that growth pattern, then protecting against climate change is a small fraction.

2) So, let me explain in more detail where my concern comes from.

a) Peak Oil (and gas) [with which I have some experience, below]

99% sure.

b) Biophysical economics models in which energy plays a bigger part in economic growth [which I am learning about].

50% sure, but rising concern.

3) Peak Oil & Gas

a) As Chief Scientist @ Silicon Graphics in the 1990s, I used to help design and sell supercomputers to climate modelers and petroleum geologists, visiting the latter in: San Ramon, Calgary, Denver, Houston, Perth, China, Bahrain, Abu Dhabi, Dubai, Dhahran, Rio de Janeiro, and a few more I’ve forgotten. This meant that I spent a fair amount of time talking about their problems, how we could help them solve them. [My undergrad background was math+physics, and I used to work summers at the US Bureau of Mines, so I could speak enough of their geology language to be useful.]

They said:

– much harder work finding oil, hence better seismic processing needed.

– need to extract a higher of fraction of oil, hence need to do a much better reservoir modeling

– and maybe find better ways to visualize the results

I probably had some hand in selling $500M worth of computers to such folks. What they said was perfectly consistent with Peak Oilers, even then.

b) I read books like

David Strahan, “The last Oil Shock”

Kenneth Deffeyes, “Beyond Oil – the View from Hubbert’s Peak”

Matt Simmons, “Twilight in the Desert”

c) Read The Oil Drum, which often has useful articles.

d) Have a long-time friend, Lord Ron Oxburgh, who was brought on as Chairman of Shell a few years ago to clean up a mess. He’s a geophysicist, a smart and direct guy, and he is *very* clear about Peak Oil (and climate change), and he was so while he was Chairman, which in general is difficult. I’ve also spoken to the Shell VP who was running the Athabasca tar sands.

e) Another friend was long time Vice-Chair of Chevron, and he certainly thinks Peak Oil is real – we spent half an hour talking about it over dinner a few weeks ago. I’ve heard the Chevron CTO (Don Paul, now retired) speak and he certainly thought Peak Oil was real as well.

f) For some reason, it is hard to find professional economists who believe 1) Peak Oil is real and 2) that it might matter, whereas petroleum people certainly think 1) and worry a lot about 2), whether they say it publicly or not.

g) Put all this together, and I am *virtually certain* that:

– Peak Oil is real, with Peak Gas another decade or two later.

– Specifically, while world oil production may jiggle around, it is *never* going to get even as much as 10% higher, and at some time in the next decade, it’s going to start dropping, and at some point, it will be dropping fast, given the way oilfields actually work, i.e., Hubbert, Deffeyes, etc aren’t too far off.

– Further out, the sensible models seem to show that by around 2050, oil production will be down to 50-60% of current.

– For various reasons, I don’t believe tar sands and shale oil are going to fix this, partly because of having talked to people who do it.

– Needless to say, for climate reasons, if we go into coal-to-liquid in any serious way, we’re in big trouble.

– Reading Kharecha & Hansen on Peak Oil & Atmospheric issues also convinces me that we’ll burn all the oil & gas, but don’t run out soon enough to stop worrying about the climate results.

When I get caught up, I’ll post the other half, i.e., why peak Oil+Gas *might* affect the usual mainstream growth rates, but certainly the 2005 DoE Hirsch Report is a start.

Anyway, IF Peak Oil+Gas don’t happen, or if they don’t matter to the US economy, then I believe the mainstream models are OK.

IF Peak Oil+Gas are real, and if they matter to the US economy, then the difference is that the US must move *even faster* to decarbonize and get more efficient, or our economy runs into a very unpleasant brick wall, which is *not* something we’re good at handling. Since I’m sure Peak Oil is real, and Soon, I sure hope it doesn’t matter.

More to come.