When will EPA fully explain and legally justify its reviews of new chemicals under TSCA?

Stephanie Schwarz, J.D., is a Legal Fellow. Richard Denison, Ph.D., is a Lead Senior Scientist.

Over two years have passed since EPA published its first, highly controversial New Chemicals Decision-Making Framework. This document attempted to lay out major changes EPA was making, in response to relentless industry pressure, to its reviews of new chemicals entering the market. Prior to this, EPA had been conducting reviews that largely conformed to the new requirements for these reviews that Congress included in the reforms to the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) enacted in June 2016.

Among the many concerning aspects of EPA’s new approach were its herculean efforts to avoid finding a new chemical “may present an unreasonable risk” or that the information available to EPA is insufficient to permit a reasoned evaluation of the chemical. Under reformed TSCA, either of those findings requires EPA to issue an order – as specified under section 5(e) of TSCA – that restricts the chemical, requires testing, or both in a manner sufficient to ameliorate the potential risk.

One of EPA’s new tactics was to illegally bifurcate its review of a company’s “intended” uses of the new chemical from other “reasonably foreseen” uses. The company would get the coveted unfettered approval to enter commerce, based on an EPA review limited to its intended uses; these approvals take the form of EPA issuing a finding that the chemical is “not likely to present an unreasonable risk.” Any review of other reasonably foreseen uses would be relegated (if it took place at all) to a later, wholly separate process that would only be triggered if EPA also promulgated a so-called “significant new use rule” (SNUR). Under such a SNUR, a company seeking to engage in a reasonably foreseen use of the chemical EPA identified would be required to first notify EPA, who would then conduct a review of that new, now “intended,” use.

These SNURs are often referred to as “non-5(e) order SNURs” because they do not follow from EPA’s issuance of an order under section 5(e) – indeed, avoiding such orders was the whole point. We have previously addressed the many problems – legal, policy, and scientific – with this approach; see for example, here and here. These include:

- the failure to assess all intended and reasonably foreseen uses of a new chemical at the same time, as required by TSCA and necessary to consider the potential for people to be subject to multiple exposures; and

- the inability to require testing of the new chemical substance using a SNUR, which can be required through an order.

EPA held a public meeting and took public comment on its 2017 Framework at the time it was published. But it never responded to the many comments it received criticizing its framework. And when EPA was sued over its use of the Framework, it dodged the suit by claiming it was not using the Framework (see p. 14 here), leading to the lawsuit being withdrawn. (Later in this post below we discuss that EPA has in fact been repeatedly using the core feature of the Framework.)

Meanwhile, hundreds of decisions made with no public framework

EPA has never made public any subsequent description of its decision-making approach or justification for it, despite the hundreds of new chemical approvals it has been cranking out ever since. EPA has also never responded to the numerous public comments it received criticizing its framework.

Frustration over this situation led to a Congressional call for EPA to publish and then take comment on an updated description of its new chemicals review process. Last January, EPA Administrator Andrew Wheeler made a commitment to Senator Carper to publish a revised new chemicals framework that would specify: “(i) the statutory and scientific justifications for the approaches described, (ii) the policies and procedures EPA is using/plans to use in its PMN reviews, and (iii) its responses to public comments received,” and to provide opportunity for public comment on the revised framework.

Last month EPA announced that it will hold a “Public Meeting on [the] TSCA New Chemicals Program,” which is to take place tomorrow, December 10. However, while the agenda includes a speaker who will provide an “overview” of what EPA is now calling its “working approach,” EPA’s announcement indicated it would not release any actual document before the public meeting; instead, it will do so “by the end of the year.” And while the meeting agenda provides for “public feedback” at the end of the meeting, the lack of any document to respond to will surely limit the ability of the public to provide meaningful input.

Absent such a public document, the rest of this post will provide our best understanding of how EPA has been reviewing new chemicals over the last two years, based on our scrutiny of each such decision.

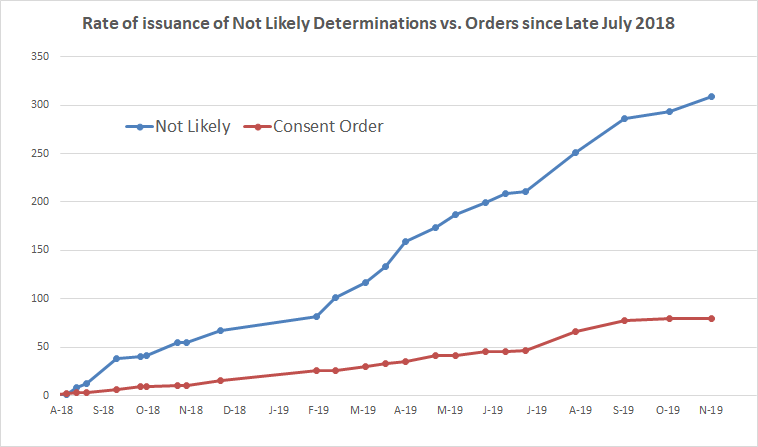

The vast majority of new chemicals reviewed by EPA since late July 2018 – which was when EPA’s new policies began to be applied – have been cleared by EPA, receiving “not likely determinations.” In what are becoming relatively rare instances, EPA still sometimes negotiates a consent order with a company, and follows it up with a SNUR – the process that the 2016 reforms to TSCA set out as the primary path but that EPA has rendered an increasingly uncommon exception.

In the period since late July 2018:

- EPA issued “not likely” determinations for 247 chemical substances.

- EPA finalized 78 consent orders. Of these, however, many were already in motion before EPA’s policies changed. Excluding these, EPA has finalized 60 consent orders.

- Hence, “not likely” determinations represents 80% of the final determinations EPA has made in that time period, while consent orders represent 20%.

Despite EPA’s claim, noted earlier, that it was not using the 2017 Framework, EPA has continued to apply its most controversial feature – clearing more than 60 new chemicals to enter the market without condition, by relying on corresponding “non-5(e) order SNURs” it has proposed at approximately the same time. The “not likely” determination documents for these chemicals specifically identify reasonably foreseen uses and state that a SNUR is to be used to address them.

The chart below shows the rate at which EPA has been issuing “not likely” determinations compared to consent orders since late July 2018, based on EPA’s own tracking statistics that we have compiled over time. The chart speaks for itself.

A new kind of SNUR emerges

Over the last few months, EPA has added an additional type of outcome involving SNURs that EPA has never publicly acknowledged nor requested public comment on. In these cases, EPA’s “not likely” determination makes no mention of a forthcoming SNUR, but at some point later, often many months later, EPA will propose a SNUR in which it states that EPA has identified “other potential conditions of use” of the new chemical; here is a recent example. To date, at least 84 new chemicals have been subject to this approach.

These SNURs include language like this (emphasis added):

[The new chemical substances] received “not likely to present an unreasonable risk” determination[s] in TSCA section 5(a)(3)(c). However, during the course of these reviews, EPA identified concerns for certain health and/or environmental risks if the chemicals were not used following the limitations identified by the submitters in the notices, but the TSCA section 5(a)(3)(C) determinations did not deem such uses as reasonably foreseen. The proposed SNURs would identify as significant new uses any manufacturing, processing, use, distribution in commerce, or disposal that does not conform to those same limitations.

This language draws attention to another aspect of EPA’s approach it has never adequately explained or justified: On what basis it determines that any use beyond the intended use specified by the submitter of the new chemical is not “reasonably foreseen.” In these new cases, EPA never identifies any “reasonably foreseen” uses, effectively eliminating a whole category of uses Congress told it to evaluate.

Moreover, it is not at all clear why the uses specified in the SNUR should not be considered reasonably foreseen. For example, EPA has approved a new chemical (P-18-0152) even though it exhibits high environmental hazard, because the submitter indicates it intends not to release the chemical to water at more than 3 parts per billion (ppb). EPA then identified as a significant new use any release to water above 3 ppb – but in doing so goes out of its way to assert that such a level of discharge is not reasonably foreseen

In any case, this additional approach still involving SNURs suffers from the same fundamental flaws of the approach set out in the 2017 Framework. While having a SNUR in place is certainly better than not having one, these are still “non-5(e) order SNURs” and nothing is in place that imposes any restrictions, only at best a notification requirement. The legality of this approach is still questionable, and all of the limitations of using SNURs in contrast to orders still apply.

Where do we go from here?

Whatever happens at tomorrow’s meeting, EPA still must provide a full, written public accounting for how it is reviewing new chemicals under TSCA: This must include both a detailed explanation of each type of decision it is making, how EPA believes that decision complies with TSCA’s requirements, and how it is at least as protective of public health as would be the case had EPA followed the more straightforward approach the law anticipated:

- Issuance of an order imposing binding restrictions on the submitter of the new chemical needed to address potential risks of both intended and reasonably foreseen uses; and

- Coupled with a SNUR that requires notification to EPA before companies can depart from those restrictions.