Without a food safety overhaul for additives, the innovative food craze could spiral out of control

Tom Neltner, J.D., Chemicals Policy Director

[pullquote]

At an FDA-sponsored conference, EDF proposed a new path forward to ensure innovative food ingredients are safe by overhauling how food additives are regulated today.

[/pullquote]Every day brings reports of new ingredients that food innovators around the world have developed to meet consumer demands for a healthier and more sustainable food supply. The innovations range from new ways to extract useful additives from existing sources such as algae to bioengineering to make novel ingredients like sweeteners or proteins that can be grown in a tank instead of on a farm.

At EDF, we encourage innovation that helps communities and the environment thrive, especially in the face of the threats posed by climate change. However, an innovator’s bold claims, especially those involving food safety, must be closely scrutinized before the additive hits the marketplace. Given the potential for harm to consumers, we cannot simply take a company’s assertion of safety at face value – there must be transparency and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) must provide an independent review.

The rise of innovative food ingredients shines a bright light on a broken system

We have seen the consequences of too little oversight play out across various industries – from the drinking water crisis in Flint, Michigan to the tragic Boeing 737 Max airplane crashes to criminal convictions for food safety violations by Peanut Corporation of America. Each has fundamentally reshaped public perceptions and continues to impact federal policy.

Unfortunately, the potential for dangerous, unintended consequences from industry self-regulation is also present when it comes to innovative food ingredients. This is due to FDA’s flawed interpretation of a loophole in the law for substances that are considered “Generally Recognized as Safe” (GRAS). This flawed interpretation allows companies to self-certify, in secret, the uses of chemical additives as safe, without notice to the agency or the public. Not only is this a shortsighted business practice, we maintain that the system FDA has established is illegal, and along with the Center for Food Safety and represented by Earthjustice, we have challenged FDA’s interpretation in court.

FDA has acknowledged the need for more oversight of innovative food ingredients in its most recent budget request when the agency said it needed $36 million in additional funds to:

- Facilitate “the safe development of these emerging technologies by investing in continued enhancements to our review capabilities for biotechnology products and other novel products;”

- Assess “these products in a risk-based manner to provide predictable commercialization pathways that can foster product innovation and market access in a safe and timely way;” and

- Improve consumer nutrition.

In addition, FDA sponsored a five-day, invitation-only conference, convened by the Institute on Science for Global Policy (ISGP), to “promote the candid exchange of ideas and clarity of priorities” regarding innovative foods and ingredients. EDF was one of eight organizations invited to present proposals regarding innovative foods and ingredients that would be evaluated by participants using ISGP’s unusual format that involves 90 minutes of debate on each proposal followed by a day of caucuses to evaluate the proposals further. The 92 participants in the conference were primarily from industry, with a mix of others from government, academia, and consumer health advocacy. In addition to EDF, the other representatives of consumer health organizations were from the Center for Science in the Public Interest (which also presented) and Center for Food Safety.

EDF’s proposal for a licensing approach to innovative food ingredients

In our proposal, we attempted to strive for a system that both ensures safe foods and encourages innovation. The proposal details a new approach Congress could adopt that replaces the current GRAS loophole with a licensing system for new food ingredients which is modeled on the process used by FDA’s Food Contact Substance Notification (FCN) program. It should be noted that the substantive details of the FCN program need to be updated to reflect current scientific principles.

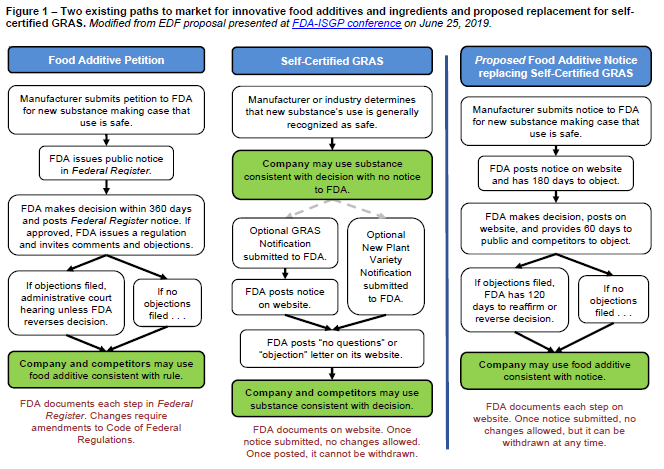

Through this process, the agency would grant a license – essentially a permit – to an innovator. The innovator allows food manufacturers to use its additive pursuant to that license. The company would need to renew the license periodically so FDA has a chance to reassess the safety based on any scientific evidence that has emerged after the license was issued. The system would complement, but not replace, the existing food additive petition option. Figure 1 below, derived from our proposal at FDA-ISGP Conference, shows how the new approach would work and compares it with the current system.

A key goal of the new approach is to provide incentives for companies to develop more rigorous safety studies to help the agency make more informed decisions. The two primary incentives are:

- Granting longer license times where the evidence of safety is stronger; and

- Giving the company the ability to restrict competitors from using those safety studies for a limited time.

An important benefit of the licensing approach is that it would make it more difficult for a copycat competitor to unfairly adopt and build upon the research and development work done by an innovator. As previously noted, under the current system, the agency posts the GRAS notice and its assessment either as a “no questions” letter or an objection on its website; other companies can freely use this publicly-available information to create a copycat product. To protect intellectual capital, some companies self-certify GRAS substances using company employees or hand-picked consultants or advisors, and forego the FDA’s critical and independent review. It is difficult to track when and where such new, self-certified additives appear in our food. Our proposal provides an incentive to go to FDA because copycat competitors would have to seek their own license from FDA.

Feedback at conference: Innovators hesitant to lose secrecy, reassessment is important as science advances

As expected in a conference dominated by industry representatives, there was significant disagreement as to whether the current regulatory system is effective at ensuring additives are safe, especially with respect to FDA’s GRAS program. In general, many innovators liked the secrecy and speed of self-certified GRAS, and many were not confident that FDA would be sufficiently timely or responsive, even with more funding to review additives. There was an acknowledgement that a systematic reassessment of past approvals had value as science advances, but there was uncertainty on the best approach. Some did not see a high-profile disaster as a risk and doubted Congress would muster the political will to overhaul the current food additives regulatory system without such an event. However, others described situations where stakeholders worked together to convince Congress to pass legislation to effectively reform policy. Participants expressed significant interest in bringing stakeholders together for “ongoing discussions to identify and proactively address concerns from all parties with regard to food safety and innovation broadly.”[1]

Some participants feared that the proposed approach would hinder small businesses from entering the marketplace because they would need to secure FDA approval before their product could be used in food. Others noted that many companies already require innovators to submit a GRAS notification for any ingredient used in their products. Participants emphasized that those companies requiring an FDA review of a GRAS notification worry that their “competitors will not demonstrate the same level of integrity and transparency, which could result in an overall negative impact on public perception.”[2]

For a summary of the discussion, please read the draft workshop proceedings on pages 121 to 132.

Next steps

Our proposal is designed to be a discussion starter. It is too soon to know whether food manufacturers and innovators could put aside their individual interests and business-as-usual philosophy and agree to constraints that creates more work –even though it could prove beneficial in the long run. And the public interest community may prefer that FDA use its broad rulemaking authority to fix the current system rather than have Congress make changes.

We firmly believe that the current system undermines consumer confidence. Further, it runs a serious risk of a tragedy that will disrupt the broader effort to help our communities and our environment thrive by bringing innovative food ingredients to market.

If you are interested, I would like to hear from you. Please contact me at tneltner@edf.org.

[1] See ISGP’s pre-publication draft of proceedings at page 128.

[2] Id.