When the lesser long-nosed bat was first listed as an endangered species 30 years ago, there were fewer than 1,000 bats in existence. Today, the bat’s population has grown to an estimated 200,000 bats living in 75 roosts across the southwestern United States and Mexico.

A lesser long-nosed bat feeding on an Agave blossom at night in Tucson, Arizona.

The lesser long-nosed bat is one of only three nectar-feeding bat species in the U.S. – uniquely providing valuable ecosystem services through bat pollination and the dispersal of fruit seeds, including for agave plants used in tequila production.

The relationship between bats and tequila may seem obscure at first, but the bat-plant association is so strong that the disappearance of one would threaten the survival of the other.

The lesser long-nosed bat is the first bat species to be removed from the endangered species list due to successful recovery. How the bat bounced back is not your typical conservation success story.

How the bat lost its (upside-down) foothold

A key threat to the survival of the lesser long-nosed bat is human disturbance of the bat’s roosting habitat – primarily caves, mines or other large crevices. The bat is a colonial roosting species, meaning hundreds or even thousands of bats can gather at a single roost. Each bat can only have one bat pup per year, making any disturbance or harm to maternity roosts especially harmful to bat populations.

The bat’s migrations and maternity roosting also rely heavily on the timed availability of foraging habitat – in this case, a key “nectar trail.” The nectar trail is the blooming and fruiting of agaves, cacti and other flowering plants along the bat’s migratory route from southern Mexico to the southwestern U.S. But this nectar trail has faced threats from an unsuspecting adversary.

A few bat species including the lesser long-nosed bat are primary pollinators of the agave plant. The agave plant has even coevolved with the bat over thousands of years, with the agave blooming at night when the bats are active. [Photo credit]

Tequila and technology save the day

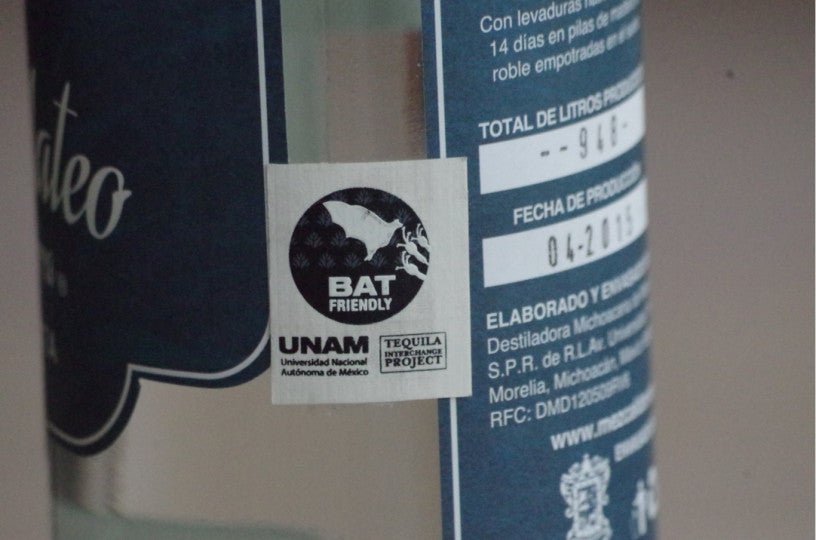

Recognizing the impact the tequila industry was having on the bat, the Tequila Interchange Project worked with agave farmers to implement bat-friendly practices. By allowing just 5 percent of agave plants to bloom, agave farms have been able to restore important feeding habitat for the bat and receive a certification for bat-friendly tequila.

The Tequila Interchange Project’s bat-friendly tequila label.

The tequila industry’s contribution to the bat’s recovery is an inspiring example of how working lands and wildlife can support one another, especially for species that provide valuable pollination services.

In addition to these conservation activities, wildlife agencies in both the U.S. and Mexico have been able to effectively protect roosting sites using installation of protective fencing to minimize human disturbance, as well as applying advanced technology to monitor bat movement.

By using radio telemetry and infrared videography, scientists have gained a better understanding of where bats are roosting, even as they migrate. Roosting sites, especially maternity roosts, can be better prioritized and protected thanks to this improved data.

As satellite technology and sensors for wildlife tracking grow more sophisticated, protection of roosting and foraging habitat for the lesser long-nosed bat and other bat species can become even more efficient.

Thanks to the efforts of agave farmers and U.S. and Mexican wildlife agencies, the lesser long-nosed bat can be considered “lesser” no more. And all of us can feel a little better about drinking margaritas (made with bat-friendly tequila, of course).

One Comment

Now, I hope they also treat good and the possible closest to fair pay to the jimaderos!