With an incoming Biden-Harris administration, many Americans are hopeful for a complete reversal of the Trump administration’s assault on climate and environmental progress at the federal level. While that change in federal leadership will be game-changing for the U.S., we cannot forget about the progress that state leaders have made on climate these last four years. It is imperative — for our health, economies and ecosystems — that we continue to hold them to it.

To curb the most catastrophic impacts of climate change — from species collapse to financial breakdown — we must meet an incredibly ambitious timeline for reducing emissions. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), reducing global emissions to around 45% below what they were in 2010 by 2030 and continuing to reduce emissions dramatically through 2050 is consistent with a path that can avert devastating impacts of climate change.

Meeting those targets will require strong action at every level of government and from every sector of the economy.

A new report by Environmental Defense Fund using emission projections data from Rhodium Group’s U.S. Climate Service shows that, collectively, states that have made climate commitments are not on track to bring their emissions down consistent with science-based trajectories for 2030. They are also off track for achieving the original U.S. commitment under the Paris Agreement for 2025. This report also reveals key insights about these states’ progress, as well as recommendations for turning goals into policies that can get the job done.

State progress amid federal inaction

Before diving into the findings, it is critical to understand the role that states have played in U.S. climate action. Over the last four years, the Trump administration has dealt a series of devastating blows to climate progress: withdrawing the U.S. from the Paris Agreement, repealing the Clean Power Plan to slash power plant emissions, rolling back Clean Car Standards, eliminating rules to limit potent methane pollution from oil & gas production, and more. All of this has happened as Americans have increasingly seen climate change take form in stronger hurricanes, wildfires and heat waves in their own backyards.

Many governors and state leaders have admirably stepped up to fill the void: 25 governors have joined the U.S. Climate Alliance, a bipartisan coalition of states and Puerto Rico committed to implementing policies that advance the goals of the Paris Agreement, including achieving reductions of at least 26-28% below 2005 levels — our intended near-term contribution. Louisiana, which is not a part of the alliance, also agreed to reach reductions 26-28% below 2005 levels by 2025. Many of these states also have committed, either by executive order or in statute, to additional reductions by 2030 and 2050. Together, all of these states represent an economy that ranks third in the world behind the U.S. and China and make up about 42% of total U.S. emissions.

But beneath the high-level commitments, how much progress are states actually making on curbing emissions?

Key findings from the report:

1. States with climate commitments face a substantial emissions gap in 2030

While a number of states have committed to net zero by 2050, staying on track with trajectories that limit climate damages requires meeting key interim goals, such as the 45% reduction below 2010 by 2030. Therefore, 2030 is a critical reference point for assessing progress at the pace and scale that’s required — and some states have also explicitly set targets generally consistent with this trajectory

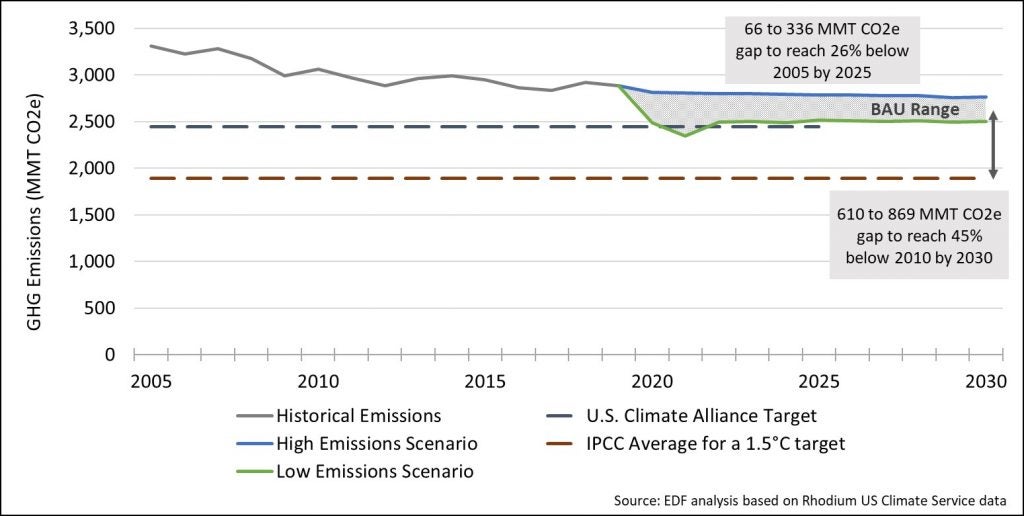

Unfortunately, our report finds that by 2030 these states are collectively projected to reduce emissions only by 11% from 2010 levels — rather than the 45% needed to achieve reductions consistent with this target. These states are also projected to face an emissions gap in 2025, in which the original U.S. commitment under the Paris Agreement calls for reducing emissions 26-28% below 2005 levels. Here, states are projected to reduce emissions by only about 18% below 2005 levels by 2025.

The historical emissions and emissions projections for 25 states and Puerto Rico in relation to the 2030 and 2025 reduction goals. We present a range of emission projections based on different economic recovery scenarios as provided in Rhodium Group’s U.S. Climate Service data, including a high emissions scenario, in which there is no COVID-19 and a low emissions scenario, which reflects a series of economic lockdowns that slow economic recovery for an extended period. We calculated the MMT CO2e gap using Rhodium Group’s V-shaped economic recovery scenario to represent a mid-range case.

Looking at total U.S. emissions, if this group of states were to close these gaps, they could bring the entire country closer to its climate goals: shrinking the remaining gap in 2030 by nearly half and cutting the 2025 gap by a third.

2. Progress varies by state

Our report highlights four states in different regions — Washington, Colorado, Minnesota and North Carolina — with varying policy and political environments to gain a better understanding of where roadblocks lie. Each of these states has taken a different approach to target setting: Minnesota and Washington have reduction goals set in statute, Colorado’s reduction targets are also statutory but carry a mandatory directive to promulgate regulations to meet them and North Carolina’s goals have been set via executive order. Nevertheless, they all have yet to take these targets from paper and put the policy framework in place that will deliver. This means assigning responsibility to specific sources and sectors of the economy through statutory or regulatory requirements that result in quantifiable, definite reductions in pollution.

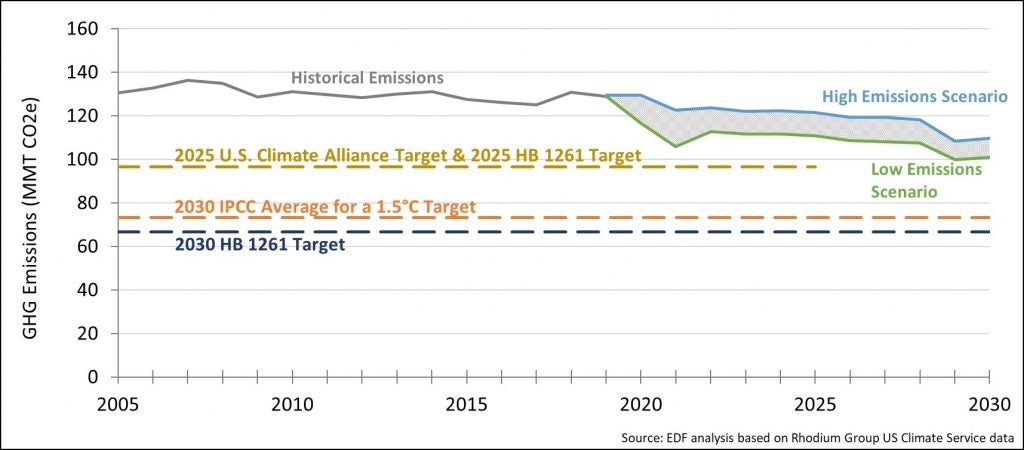

For example, the Colorado legislature passed a suite of landmark climate policies over a year ago. While state regulators were required to propose regulations that would allow the state to meet its goals this past July, state officials have instead focused on compiling a comprehensive catalogue of the technological and systems changes needed across the economy and haven’t yet developed of the regulations necessary to limit pollution the requisite amount. Consequently, Colorado faces an emissions gap in 2030 ranging from 28-37 MMT CO2e, despite having passed one of the strongest pieces of climate legislation in the country.

Colorado’s historical emissions and projected emissions in relation to the 2030 and 2025 reduction goals. The state faces a 28-37 MMT CO2e emissions gap in 2030.

On the east coast, North Carolina faces a similar analysis paralysis: Gov. Cooper first issued his climate directive in October 2018, but has yet to direct agency action to implement the policies that will ensure persistent reductions over time. This lies in contrast to North Carolina’s neighbors to the north: Pennsylvania and Virginia have been busy putting regulatory programs in place that limit pollution from their power sector — both states’ largest emissions sources.

And in the middle of the country, Minnesota has had climate reduction commitments longer than nearly any state — their goals were put into statute in 2007 by then Gov. Tim Pawlenty. Yet despite early leadership, Minnesota is not on pace to secure the reductions envisioned — and recently has been at a standstill. Despite expansive existing authority to tackle climate pollution stemming, and the growing impact of extreme heat on the state’s agriculture, emissions are projected to rise over the next decade and no regulations have been adopted to drive reductions consistent with their targets.

3. Policies that can help close the emissions gap

While each state has a unique political and geographical environment, our report identifies several key ways they can close the gap:

- Establish a declining, enforceable limit on GHG emissions: These limits should serve as a backstop, covering emissions from all of the state’s major sources of pollution, and can be source based, sector based or applied across multiple sectors. For example, 10 states in the Northeast and mid-Atlantic have been successfully reducing carbon emissions from the power sector through the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI).

- Ensure environmental and economic benefits are directed to disproportionately-impacted communities: Alongside and as part of an emissions limit framework, states should ensure that benefits from investments in a clean energy future, including improvements in local air quality, are directed to communities most overburdened by pollution and to communities impacted by the transition away from fossil fuels.

- Evaluate progress based on emissions metrics: States should calibrate their climate policies toward securing reductions consistent with clear reduction trajectories that decline immediately, and persistently, over time. And they should ensure their policy framework is capable of controlling cumulative emissions of long-lived pollutants over the critical upcoming decade, aligning total reductions over this time period with the IPCC’s estimated carbon dioxide budgets.

- Consider an approach that puts a price on pollution: If well designed, using a carbon price to help meet pollution limits can enable much greater ambition by securing the most cost-effective reductions, jumpstarting innovation, and accelerating early action—which critically will help maximize cumulative emission reductions.

- Catalyze the development and deployment of clean technologies: Supporting the ongoing adoption of performance-oriented policies can accelerate the development and deployment of clean technologies in conjunction with an emissions limit — cleaning up our cars and buildings —and making the limits on pollution easier to achieve over time.

The opportunity at hand

Governors and state leaders have made vital efforts to keep climate momentum moving forward, and they are far ahead of states where leadership has failed to demonstrate any commitment to act.

But these leaders who have made commitments must hold themselves accountable to delivering real progress on emissions. Carbon pollution, after all, can remain in the atmosphere for thousands of years. Major action now — particularly with policies that are capable of enhancing cumulative reductions over the upcoming decade — can be life-saving in terms of averting long-term climate damages.

The coming months present an opportune time to accelerate progress: As state and federal leaders develop plans to rebuild and revitalize the economy in the wake of COVID-19, they can invest in a clean economy that curbs climate pollution and protects disproportionately-impacted communities. With 10 years to deliver the most significant reductions in climate pollution and get on track to achieve net-zero emissions across the U.S. economy no later than 2050, state leaders cannot afford to take their foot off the pedal now.

States have the authority and the opportunity to drive down emissions; the urgency and scale of the problem demands their leadership.

Read the full report on states’ emissions progress.

2 Comments

merci

thanks for this is infourmation